BY CHRIS SLAY

A quart of very fresh wildflower honey will taste like a sunny summer day all year long.

A quart of very fresh wildflower honey will taste like a sunny summer day all year long.

During the honey flow period, many established colonies made more honey than they need. In this four-part series, we’ll explore exactly what honey is, what differentiates some honey from others, traditional and modern medical uses, and the rich history humans have with honey as a food source. We’ll also disprove some common misconceptions about honey. Welcome back to the fascinating life cycle of the honey bee.

Honey begins as nectar from flowers. Worker bees collect nectar and pollen for food. The nectar that isn’t immediately consumed is stored in bees’ honey bellies and taken back to the hive. Honey bees’ salivary enzymes and proteins break down the nectar’s complex sucrose and starches into simple, more quickly digested sugars — glucose and fructose.

Because wild yeasts and bacteria can easily live on nectar, robbing its nutrients, honey bees reduce the nectar’s water content in two astonishing ways. First, they repeatedly regurgitate the nectar into their mandibles to create bubbles that provide a large surface area for water to evaporate. Second, after storing the partially dehydrated solution in open wax cells, groups of workers will constantly fan their wings, producing heat and airflow to reduce the water content even further. After the solution lowers to a water content of 18% to 15.5%, bees cap the cells with wax.

The nectar is now beyond the saturation point of water. This means there is far more sugar dissolved in what little water remains than ever could be dissolved in an equivalent volume of water.

For example, it’s impossible to dissolve one cup of sugar in seven teaspoons of water. This is honey.

Honey’s supersaturation of sugar is incredibly stable on molecular and chemical levels. Yeasts and bacteria are deterred from living on honey while in the capped cells, which ensures a very fresh and untainted food source.

The type of honey a colony produces depends entirely on the nectar’s primary source. Wildflower, the most abundant type of honey, is a combination of all of the thousands of different flowers from which the bees forage. Wildflower honey is typically light to dark amber in color and can have a very complex, multi-faceted taste. Other local nectar sources, such as basswood, tulip poplar, and sourwood trees, produce a much lighter-tasting, grassy-golden honey. Regardless of what the label says, no one knows what other flowers’ nectars are present without microscopically identifying the unique pollen cells in honey. Bees don’t discriminate.

At retail, honey is offered in many forms, but it’s either raw or processed. Most commercially produced honey is pasteurized, which ensures bacterial decontamination that may occur after uncapping the cells for extraction and the packaging process. Raising the temperature of honey above 104F also diminishes many of the unique qualities of honey. If you’ve ever had milk fresh from the cow, you understand. Commercial honey may also contain additives like high-fructose corn syrup or artificial coloring.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: All about honey – part 1 | Community News | thetomahawk.com

]]>By: Gard W. Otis

The Yellow-legged Hornet, Vespa velutina, has been discovered in the state of Georgia! This social wasp, native to Asia, preys extensively on honey bees and other pollinators. Its arrival in North America, while not wholly unexpected, is a cause for alarm for beekeepers and agriculture in general. What is this wasp? Why is it a concern? What can we do to control it? And how concerned should we be at this time?

Figure 1. Yellow-legged Hornet, Vespa velutina, at rest. Photo taken in France, courtesy of Patrick Le Mao

Figure 1. A Yellow-legged Hornet hovers in front of a hive, awaiting incoming forager bees. Photos taken in France, courtesy of Quentin Rome / Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France.

V. velutina is a large wasp, approximately 0.7–1.0 inch (1.7–2.5 cm) in length and with distinctive yellow legs (Fig. 1). It is a social insect, with colonies composed of numerous workers and a slightly larger queen (Pérez-de-Heredia et al., 2017). The species has been studied extensively, both within its native range and in the regions of western Europe, South Korea and Japan it has invaded. Its colonies, founded by a single mated queen, become more populous as Summer progresses. By late Summer, its large, round papery nests, usually concealed by leaves in tree-tops, contain hundreds of worker hornets. To feed their larvae, they capture a wide variety of insects, with the Western Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) being a favored prey species, in part because stationary honey bee colonies provide food consistently for weeks on end (Fig. 1; Roy, 2023). Laurino et al. (2020) provided a review of the biology of the species and its invasion of Europe, where programs to control the species cost millions of dollars annually.

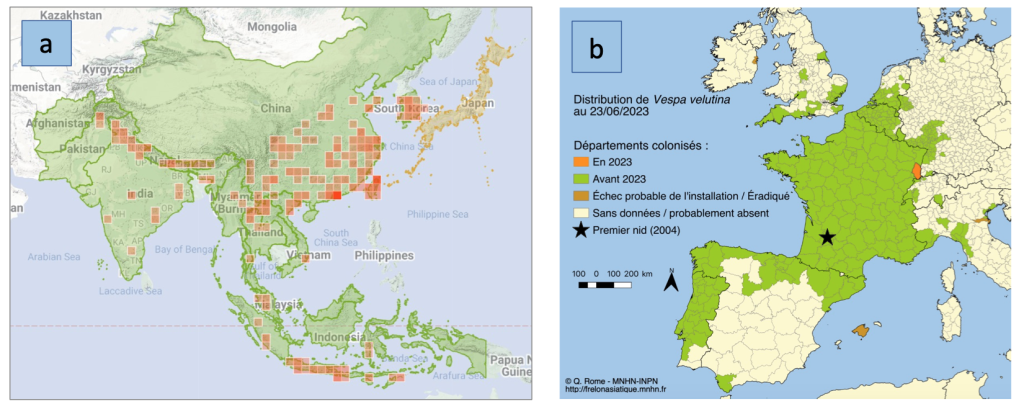

Figure 2. Distribution of V. veluntina (a) in Asia where it occurs naturally and has been introduced to South Korea and Japan, and (b) in Europe where it has been introduced. The red dot indicates where the first hornets were discovered in 2004. (Maps from (a) iNaturalist.org and (b) INPN (2023), used with permission of Quentin Rome / MNHN

Vespa velutina naturally inhabits a region that extends from northern China south through Indonesia and Southeast Asia, and westward along the foothills of the Himalayas to Afghanistan (Fig. 2a). Over that range, it occurs in 13 different color forms (formerly referred to as subspecies). It is likely that the hornets in Georgia are of the northern mainland form, V. velutina nigrothorax, that has also invaded Europe (Fig. 2b) and northeastern Asia. V. v. nigrothorax has often been inappropriately referred to in much of the literature written about it as the “Asian hornet”, a misnomer given that all 22 species of hornets inhabit some part of Asia!

The life cycle of the Yellow-legged Hornet is generally the same as that of all species of hornets (i.e., wasps in the genus Vespa) in temperate climates (Laurino et al., 2020). A mated queen emerges from her wintering site and becomes active in Spring when the weather becomes suitable. After a period of feeding on floral nectar and tree sap, followed by dispersal estimated to exceed 30 miles (50 km) in some instances, she individually constructs a small comb enclosed within a papery envelope made from plant fibers she chews and mixes with her saliva. The queen then rears the first generation of hornets by herself in an “embryo nest.” When those first workers have completed their development and emerge as adults, they take over most colony activities (nest construction, brood care, foraging and colony defense) while the queen continues to lay most, if not all, eggs. Towards Fall, the colony rears new queens and males. Those new queens mate with males, search for a wintering site that is usually in soil, leaf litter or rotten wood, and become quiescent for several months while temperatures are too cool for activity. It is while they are in Winter diapause that the queens can be accidentally transported long distances as stowaways among cargo on ships and, less frequently, on planes. This is almost certainly how Yellow-legged Hornets arrived in Georgia: the sites where the first individuals were discovered are within 12 miles of the Port of Savannah, one of the largest shipping ports in North America that receives cargo from everywhere in the world.

One important difference between the Yellow-legged Hornet and other species is the relatively large number of males with which young queens mate. The majority of hornet species that have been studied, mate with one or sometimes two males. In contrast, V. velutina queens mate with three males on average (range from one to 5+). The invasion of Europe by this species is believed to have originated from a single queen, mated with four males, that was accidentally imported to southwestern France (Fig. 2b). The added genetic variability provided by mating with several males has undoubtedly contributed to its successful invasions (reviewed by Otis et al., 2023).

Vespa velutina colonies can become very large. Quentin Rome and his colleagues (2015) collected nests in southwestern France from June to November and quantified their populations of immature and adult hornets. The colonies, generally initiated in March, had an average of 440 worker hornets by late October and early November. Some of those nests remained very small, but the most populous colony had 1,740 workers (News reports that colonies may contain 6,000 or more workers are erroneous). Mature colonies in Fall contained an average of 190 new queens (Rome et al., 2015), but because young queens only remain in their nest for about two weeks, that number must represent only a portion of all queens reared. I estimate that the average number reared is approximately 300–400 per colony. The greatest number of new queens collected inside one single nest was 463.

In an odd quirk of biology, hornet larvae serve as reservoirs of food within their colony. Larvae convert the proteins in chewed-up insect prey collected by worker hornets into amino-acid rich sugars. They then feed those secretions to young queens, resulting in them increasing in weight by 20–40% within one to two weeks of emergence as adults due to deposition of fat that fuels their survival during several months of Winter diapause. Young males also require the nutrients provided by larvae in order to mature sexually. Because hornets do not store honey in their nests, the sugary secretions from larvae also sustain their colonies during periods of inclement weather when foraging is not possible (reviewed by Otis et al. 2023).

How does the Yellow-legged Hornet affect honey bees and other pollinators?

The greatest concern related to the establishment of Yellow-legged Hornets in North America is their effects on honey bees and other pollinators. These hornets capture a wide variety of flying insects, a high percentage of which are pollinators, to feed to their larvae. Honey bees in particular are heavily preyed upon. Hornets hover near a hive entrance, facing outwards, so they can pick off incoming foragers (Fig. 1). Once a hive has been located, a hornet can return repeatedly to prey upon the essentially defenseless honey bees. Dr. Yves Le Conte, former head of the French honey bee research unit in Avignon, told me that by late Summer, when honey bees colonies should “prepare good Winter bees and collect honey for Winter survival, the hornets put pressure on the bees.” Hornets seem to focus on weaker colonies and in some cases, once they have killed most of the bees in a hive, they may enter and eat both the brood and the honey. In addition to the constant attrition of foraging bees, the presence of multiple hornets at the entrance of a colony causes “foraging paralysis” in extreme cases, flight activity is completely suppressed. The reduced foraging results in low honey stores and Winter starvation, with losses of 30–50% often reported (Yves Le Conte, pers. comm.; Requier et al., 2019). This hornet is a very significant threat to honey bees!

What has happened in Georgia in 2023?

From the information I have been able to obtain, Yellow-legged Hornets were first observed on or before August 1st by Sarah Beth Waller (personal communication), the beekeeper at the Savannah Bee Company on the eastern edge of Savannah where they were feeding on fallen pears. She posted a photo to iNaturalist on August 7th that yielded a tentative identification of the hornet as Vespa velutina (iNaturalist, 2023). Also in early August, a beekeeper somewhere in Savannah (at a date and location that have yet to be revealed by the Georgia Department of Agriculture) collected two hornets as they visited his hives. They were identified first by a University of Georgia entomologist and subsequently confirmed by the USDA on August 9th (GDA, 2023a). Thanks to news reports on August 15th about this discovery, a homeowner in the vicinity of the Savannah Bee Company reported a large nest 75 feet up in a pine tree. That nest, destroyed on the evening of August 23rd, proved to be exceptionally large (GDA 2023a, b). Keith Delaplane (University of Georgia) informed me that hornet traps of an unknown type have been deployed by the GDA from Port Wentworth to the mouth of the Savannah River, a distance of 18 miles. One person I interviewed was of the understanding that the first two locations where the hornets were observed are approximately eight miles apart, which, if true, would suggest that additional colonies may be present (hornets usually forage within a mile of their nest). Hornets have been sent for genetic analysis to determine if they originated in Europe or Asia. The situation in Savannah is fluid and changing rapidly. By the time this article is published, much more will be known and divulged. It may take a year or more before we know whether this incipient infestation has been eradicated.

What can be done to reduce the threat posed by the Yellow-legged Hornet?

Traps of many designs have been developed and tested in Europe. They have proven moderately effective for monitoring the presence of the hornet, but do not catch sufficient hornets to appreciably affect established colonies. Moreover, they have been criticized for their extensive by-catch of non-target insects. If the traps that have been deployed in Georgia capture additional hornets, finding and destroying their nests before new queens disperse into the environment presents the greatest probability of successful eradication. As an example, in spite of repeated discovery of Yellow-legged Hornet colonies in southern England, coordinated efforts of agricultural personnel, beekeepers and scientists have so far been successful at preventing the wasp’s establishment in the United Kingdom (Jones et al., 2020). On the Mediterranean island of Mallorca, the combination of Spring trapping of gynes before they establish nests, baiting for foragers, and triangulating and destroying colonies before they produce new queens, eliminated the initial infestation. There have been some successes in using very light-weight radio transmitters to track Vespa hornets to their nests (Kennedy et al., 2018; Looney et al. 2023). After a few years, however, once a population of hornets has become established, the proportion of nests that can be found and destroyed has proven in several European countries, to be insufficient to control the invasion.

Monitoring by state departments of agriculture (e.g., see the online form set up for reporting in Georgia; GDA 2023a) or through community-scientist platforms such as iNaturalist can provide accurate reporting of exotic hornets and other pests. Beekeepers can play a huge role in early detection of non-native hornets because several species that have the potential to become established in North America prey extensively on honey bees. Any wasp that seems unusual can be photographed or caught in a jar, then compared with similar species (USDA-APHIS, 2023). It should be reported if you suspect it is V. velutina or another non-native species.

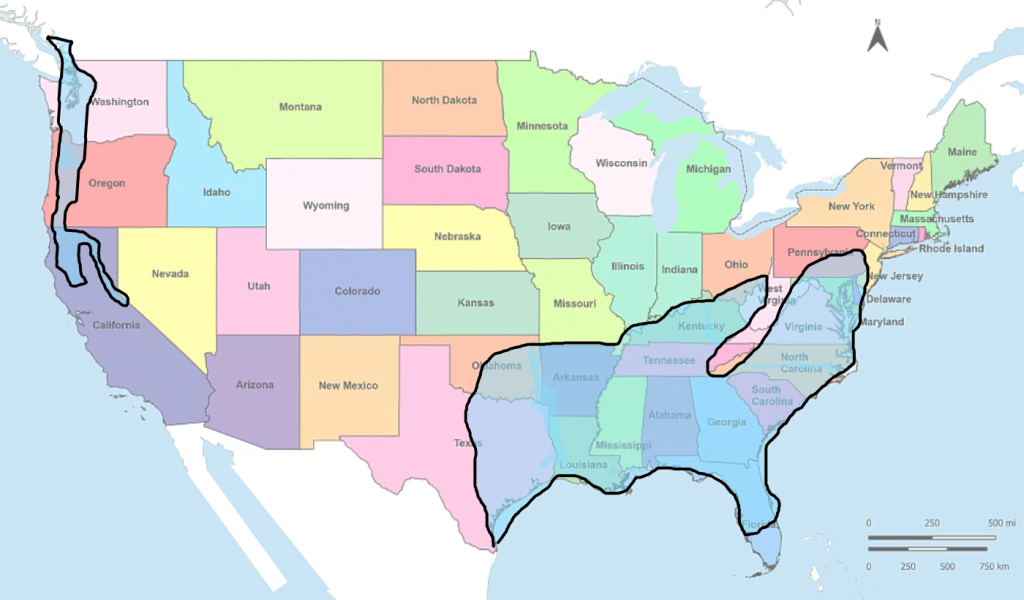

Figure 3. Regions of North America with climate well suited to Yellow-legged Hornet survival. Other regions with lower climate suitability not shown. Adapted from Villemany et al. (2011).

Where is the Yellow-legged Hornet likely to survive in North America?

GIS technology coupled with climate data for localities throughout the world that are available online have revolutionized our ability to predict potential distributions of species outside of their native ranges. In the case of the Yellow-legged Hornet, climate variables from where the species has been documented in Asia as well as in its introduced range in France, were analyzed along with climate data for sites throughout the rest of the world. A map showing the probability of suitable climate for hornet survival was created (Villemant et al., 2011). I superimposed the North American portion of that map onto a map of the United States, then modified it to show the approximate regions in North America where Vespa velutina would almost certainly be able to survive and reproduce (Fig. 3).

A large area of southeastern USA is predicted to have climate suitable for V. velutina. That region extends from the southern tip of Texas north into Oklahoma, then eastwards to somewhere between Baltimore and New York (Fig. 3.). Hornet survival may even be possible as far north as Boston and southern Ontario (Villemant et al., 2011). On the west coast, there is a zone in the rain shadow of the coastal mountains, from Vancouver, Canada, south into California, that seems prone to invasion. The hornet is likely to do better where the minimum temperature in Winter is not too cold, relative humidity is fairly high and the maximum temperature in Summer is not too hot.

Figure 4. The Northern Japanese Hornet, Vespa mandarinia, a species that invaded the Pacific Northwest in 2019. Photo taken by Aline Horikawa near Kyoto, Japan, and used with her permission.

What about other exotic species of hornets?

Who can forget the “invasion by murder hornets” in 2019–2021? The Northern Giant Hornet (formerly known as the Asian Giant Hornet), Vespa mandarinia, is a huge social hornet (Fig. 4; also, refer to the image within YLH lookalikes” in USDA-APHIS, 2023) that is infamous for its ability to rapidly slaughter entire colonies of Apis mellifera. Its discovery in Fall of 2019 led to an extensive monitoring and eradication effort that is on-going in Washington state and British Columbia. Following a peak of 35 sightings and specimens in 2020, there were only 10 reports in 2021 (Looney et al., 2023). Since then, there have been no Northern Giant Hornets detected in North America, and there is optimism that the introduction of this species has failed. It is not clear what combination of factors is responsible for the decline in its population: relatively unsuitable climate, low genetic diversity, destruction of nests (one in British Columbia, four in Washington state; Looney et al. 2023) or other factors. It is known that relatively few species that reach foreign lands are successful in establishing permanent populations. We may simply have gotten lucky with the recent Northern Giant Hornet introduction.

Several groups of researchers have modeled the potential distribution of V. mandarinia. All of them yielded a strong probability of it surviving in the Pacific Northwest where it was initially discovered as well as a large region of eastern North America; however, these models fail to agree on the regions in the east that are most prone to invasion. Because this species focuses its predation in late Summer and Fall on social insects, including honey bees, beekeepers are again the group most likely to encounter it. If you see any wasp attacking and killing honey bees, you should report it immediately.

Figure 5. The Oriental Hornet, Vespa orientalis, a demonstrated invader in northern Italy, southern France, Sardinia, southern Spain, eastern Europe and Chile. Photo taken by Nicola Addelfio near Palermo, Sicily, Italy, and used with her permission.

The Oriental Hornet (Vespa orientalis: Fig 5.), naturally inhabits the Mediterranean, Middle Eastern and western Asian countries and is the only hornet species adapted to hot, arid climates. This striking reddish brown hornet is an agricultural pest that attacks honey bee colonies and damages fleshy fruits such as grapes. It has already been detected in at least 10 countries outside of its native range (reviewed by Otis et al., 2023), and has successfully colonized southern Spain and Chile. Young queens often Winter in groups (Eran Levin, pers. comm.), a behavior which may have helped it to overcome genetic bottlenecks. Species distribution modeling suggests it has a high probability of successfully colonizing the Gulf Coast region of the United States as well as central California.

I would be remiss not to mention the European Hornet, also a large wasp that could be mistaken for one of the other species mentioned (USDA-APHIS, 2023). It was accidentally introduced to New York City nearly 180 years ago and has become relatively common in much of Eastern North America, but because it rarely captures honey bees and has relatively small colonies, it has not proven to be a concern for beekeeping.

Conclusion

Several hornet species cause extensive damage to honey bee colonies in other parts of the world. Unlike Varroa mites and small hive beetles, hornets do not inhabit bee colonies and would be very unlikely to be transported with hives when they are moved for pollination. However, they do have the potential to arrive at any port and subsequently be transported by trucks and trains anywhere in North America! The establishment of any of the exotic hornets discussed before would cause extensive disruption to beekeeping due to their predation on bees and secondary effects on Winter colony survival. The propensity of these hornets to attack honey bees makes beekeepers the most likely people to encounter them, as demonstrated recently with the detection of the Yellow-legged Hornet in Georgia. Readers are encouraged to learn how to identify them: review the figures in this article and “lookalikes” in USDA-APHIS (2023). Stay vigilant—and let’s hope that we remain “hornet-free” for many years to come.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Lien T.P. Nguyen of Vietnam and Heather Mattila of Wellesley College, MA, my hornet research collaborators, for the knowledge and experiences they have shared with me over the past decade. Staff at the University of Georgia, K. Cecelia Sequira of USDA-APHIS, and Sarah Beth Waller shared important information about the Yellow-legged Hornet detection in Georgia up until 27 August, 2023. I must also recognize the dozens of wasp biologists worldwide who have willingly answered my many naive questions about hornets.

Gard W. Otis

School of Environmental Sciences, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada

Institute of Bee Health, University of Bern and Agroscope, Bern, Switzerland

Selected References

GDA (2023a). Georgia Department of Agriculture press release (Aug. 25, 2023). https://agr.georgia.gov/pr/yellow-legged-hornet-nest-eradicated-savannah-area

GDA (2023b) Georgia Department of Agriculture press conference (Aug. 25, 2023). https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=639982398259487

iNaturalist (2023). Yellow-legged Hornet (Vespa velutina). https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/119019-Vespa-velutina

INPN (2020). Le frailon asiatique, Vespa velutina. (The Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina). Inventarie National du Patrimoine Naturel. (http://frelonasiatique.mnhn.fr/)

Jones E.P., C. Conyers, V. Tomkies, et al. Managing incursions of Vespa velutina nigrithorax in the UK: an emerging threat to apiculture. Scientific Reports (2020) 10:19553. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76690-2

Kennedy P.J., S.M. Ford, J. Poidatz, et al. (2018). Searching for nests of the invasive Asian hornet (Vespa velutina) using radiotelemetry. Communications Biology 1: 88. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0092-9

Laurino D, S. Lioy, L. Carisio, et al. (2020). Vespa velutina: an alien driver of honey bee colony losses. Diversity (2020) 12: 1–15. doi:10.3390/d12010005

Looney, C, B. Carman, J. Cena, et al. (2023) Detection and description of four Vespa mandarinia (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) nests collected in Washington State, USA. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 96: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.96.99307

Otis, G.W., B.A. Taylor, and H.R. Mattila (2023). Invasion potential of hornets (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Vespa spp.). Frontiers in Insect Science 3: 1145158. https://doi.org/10.3389/finsc.2023.1145158

Pérez-de-Heredia, I, E. Darrouzet, A. Goldarazena, et al. (2017). Differentiating between gynes and workers in the invasive hornet Vespa velutina (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) in Europe. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 60: 119–133. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.60.13505

Requier, F., Q. Rome, G. Chiron, et al. (1019), Predation of the invasive Asian hornet affects foraging activity and survival probability of honey bees in Western Europe. Journal of Pest Science 92: 567–578.

Rome, Q., F.J. Muller, A. Touret-Alby, et al. (2015). Caste differentiation and seasonal changes in Vespa velutina (Hym.: Vespidae) colonies in its introduced range. Journal of Applied Entomology 139: 771–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12210

Roy, H. (2023). BBC. Asian hornet guide. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/insects-invertebrates/asian-hornets-guide/

USDA-APHIS (2023). Yellow-legged Hornet. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/plant-pest-and-disease-programs/honey-bees/yellow-legged-hornet (accessed 25 August, 2023).

Villemant C., M. Barbet-Massin, A. Perrard, et al. (2011). Predicting the invasion risk by the alien bee-hawking yellow-legged hornet Vespa velutina nigrithorax across Europe and other continents with niche models. Biological Conservation 144: 2142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.04.009

Propolis is a sticky resinous substance found in bee hives.

Beekeepers look to untapped potential of propolis, or ‘bee glue’, as alternative revenue stream

A by-product of honey production largely discarded in Australia could provide an alternative income source for beekeepers across the country.

Hidden within the walls of their hives, bees blend up a unique mix of materials that scientists believe holds untapped potential in Australia.

Propolis is a sticky, resinous substance that’s sometimes referred to as “bee glue”.

Bees use propolis as a powerful sterilising agent as well as to seal gaps in their hives against predators and the elements.

‘Propolis is used by the bees because they don’t have an immune system,” Queensland beekeeper Murray Arkadieff said.

“Bees forage within a 7 kilometre radius of the beehive, so that means they cover about 210km²,” he said.

Murray Arkadieff has been a beekeeper his entire life.

Mr Arkadieff said the bees were able to look throughout that 210km² and search for parts of plants that could be used to polish their hives.

The bees not only forage for nectar and pollen, but also for other parts of the natural environment such as sap or bark.

“They bring that back to the beehive and they can mix it all together and it turns it into a really strong antimicrobial, anti-fungal, antiviral and antibacterial material, which they polish their entire hive with,” he said.

Propolis and its medicinal wonders

Propolis also has benefits for people and is used in many different countries in medicines, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

“Propolis contains high polyphenolic compounds,” organic chemist from the University of the Sunshine Coast Trong Tran said.

“Australian propolis is very diverse and it also shows very comparable, even higher antioxidant activities compared with the other well-known propolis in the world, Dr Tran said”

Despite being part of a well-established industry elsewhere, in Australia there isn’t large-scale commercial propolis harvesting and processing.

“We’ve always mainly been focused on liquid honey production,” Mr Arkadieff said.

“It’s not something that Australians have looked into in a massive way, which is why it’s such an exciting opportunity for the industry.”

Peter Brooks is part of the research team from the University of the Sunshine Coast that has been part of the Australian Propolis Project, an initiative supported by the federal government’s Agrifutures organisation.

“When we started talking to beekeepers about what they were interested in they were saying: ‘Well this propolis product that they throw out, it’s got a lot of value, so how could we use that in some of our research?” Dr Brooks said.

Samples of propolis were collected from different areas around the country and were sent to the lab to be analysed.

“Like everything, if you’re throwing something away that you could be making money for — it could be a new source of income.”

To begin with, scientists needed to ensure that Australian propolis was valuable, given its specific properties were largely unknown.

A buzzing opportunity for beekeepers

Hive and Wellness Australia, formerly known as Capilano, asked its 1,200 beekeepers nationally to consider participating in a trial collection of propolis.

Samples collected from all over the country were sent to the University of the Sunshine Coast for analysis.

“Of those samples that came back I think there was around 55 per cent that showed high antioxidant compounds,” said Jessica Berry, an industry liaison officer with Hive and Wellness Australia.

Dr Tran leads the research team, which is focused on finding out which samples hold the higher antioxidant value, and why.

He thinks one reason might be that about 80 per cent of Australia’s plants are endemic, and so aren’t found anywhere else.

“So we can expect that Australian propolis is unique to other areas in the world,” he said.

The complete article can be found at; https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-23/australian-beehives-propolis-alternative-revenue-for-beekeepers/102625256o

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-23/australian-beehives-propolis-alternative-revenue-for-beekeepers/102625256o

]]>The sweet stuff can help with burns, coughs, anxiety and more

By Alison Gwinn,

AARP

Photo by Daily Slowdown on Unsplash

Honey’s benefits have been touted since antiquity — and it turns out the ancient Greeks and Romans were onto something: Honey really can hit the sweet spot when it comes to our health.

Though honey — a sweet, sticky liquid made by honeybees from flower nectar — is technically a sugar, “it’s also really rich in a lot of different bioactive substances,” says Mayo Clinic registered dietitian (and hobbyist beekeeper) Joy Heimgartner. Those include a range of good-for-you minerals, probiotics, enzymes, antioxidants and other phytochemicals.

There are four common types of honey: Raw honey is defined by the National Honey Board as “honey as it exists in the beehive or as obtained by extraction, settling or straining without adding heat.” Manuka honey, produced from the flowers of manuka trees, is known for its unique antibacterial properties, attributed to a compound called methylglyoxal, says Jordan Hill, lead registered dietitian for Top Nutrition Coaching.

Organic honey is produced without the use of synthetic chemicals, pesticides or GMOs. And locally produced honey has been reported to provide relief from seasonal allergies to local pollen, though scientific evidence to support that claim is limited, says Hill.

According to Hill, honey can be substituted for sugar in recipes, but remember: It has a distinctive flavor (which varies depending on the source flowers); it’s sweeter than sugar (the general rule of thumb is to use ¾ to 1 cup of honey for every 1 cup of sugar); it’s a liquid, so you may need to cut back on other liquids or slightly increase the dry ingredients in a recipe; and it browns more quickly than sugar (so reduce the oven temperature by 25°F).

But whatever way you use honey — in a recipe or as a condiment — always keep in mind that it is a sweetener. “Honey is a supersaturated sugar solution, and we should limit added sugars of all types,” says Heimgartner. Still, “if you’re looking for a sweetener that has more to offer, honey is fantastic.” Here are six reasons why.

- Honey doesn’t raise your blood sugar as rapidly as white sugar

“Honey is metabolized differently from white sugar and produces less of a sugar spike,” says registered dietitian and nutritionist Dawn Jackson Blatner, author of The Flexitarian Diet. “Research suggests that honey may enhance insulin sensitivity and may support the pancreas, the organ that produces insulin.” A 2018 review of preliminary studies points to honey’s “hypoglycemic effect” and use as a “novel antidiabetic agent that might be of potential significance for the management of diabetes and its complications.”

And a 2022 study out of the University of Toronto found that honey improves important measures of cardiometabolic health, including blood sugar, cholesterol and triglyceride levels, especially if the honey is raw and from a single source.

- Honey can help with wound or burn therapy

“Honey has been used for wound healing for centuries, and certain types of honey, like medical-grade honey, have shown potential in wound management due to their antimicrobial properties and ability to promote healing,” says Hill, who nonetheless advises consulting health care professionals for appropriate wound care. Heimgartner, a board-certified oncology specialist, says, “There’s actually a lot of evidence that using honey during oral cancer radiation treatment helps to prevent some of the nasty side effects of mucositis,” or inflammation of the mouth.

How does it work? “Research suggests that honey prevents or controls the growth of bacteria on the wound, helps to slough off dead tissue and microorganisms, and transports oxygen and nutrients into a wound for quicker healing,” says Blatner.

Native plants and naturalistic perennials attract bees and other pollinators.

Create Your Own Pollinator Garden

If you want to create your own pollinator garden for bees to forage in, consider these tips from Emily Erickson, postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis, department of evolution and ecology.

- Opt for native plants or naturalistic perennials.

- Choose plants of varying colors, shapes and bloom times so you can support a variety of pollinators throughout the season.

- Avoid double-flowered varieties (those with extra petals) or plants that look drastically different from their wild relatives.

- Avoid pesticides.

- Leave areas in your yard that can serve as nesting habitats, such patches of bare soil, brush, twigs or woody stems, where many native pollinators make their homes.

- Which plants are right for you depends on your location and climate, so ask your local nursery for advice — or simply walk through a nursery and notice which plants seem to attract pollinators.

- Honey is rich in polyphenols, including flavonoids

Why does that matter? Because those two substances have both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, meaning they protect our bodies against oxidative stress, which can manifest as cancer, heart disease or other diseases. But Hill cautions that the polyphenols in honeys can vary significantly, depending on the type of honey and its floral source.

- Honey can be an effective cough suppressant

A 2020 meta-analysis found that honey provides a widely available and inexpensive alternative to antibiotics in controlling cough frequency and severity, though it concluded that further studies were needed. “It is believed that honey’s thick texture and possible antioxidant and antimicrobial properties may provide relief for cough symptoms,” Hill says, but she adds the caveat that honey should never be given to infants under 1 year of age due to a risk of botulism.

- Honey may provide antidepressant or anti-anxiety benefits.

“Research suggests that polyphenol compounds in honey such as apigenin, caffeic acid, chrysin, ellagic acid and quercetin support a healthy nervous system, which may enhance memory and support mood,” says Blatner. Though more study is needed, a 2014 review of research says that one established nootropic (or cognitive-enhancing) property of honey “is that it assists the building and development of the entire central nervous system, particularly among newborn babies and preschool-age children, which leads to the improvement of memory and growth, a reduction of anxiety, and the enhancement of intellectual performance later in life.”

- Honey may support a healthy gut

Early research indicates that “honey has an extra-special ability to support a healthy gut microbiome because it contains both probiotics, or good bacteria, and prebiotic properties, which help good bacteria thrive,” says Blatner, though the evidence is limited. A 2022 paper funded by the National Institute of Health, Malaysia, concluded that “honey bees and honey, which have the potential to be good sources of probiotics and prebiotics, need to be given greater attention and more in-depth research so they can be taken to the next level.”

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: https://www.aarp.org/health/healthy-living/info-2023/honey-health-benefits.html

]]> Fresh Broccoli with Honey

Fresh Broccoli with HoneyBy: Fay Jarrett

Ingredients

□ 4 cups chopped broccoli

□ ¼ cup honey

□ 1 tbsp olive oil (tuscan herb was used this time)

□ ½ tsp pepper

□ ½ tsp salt

Directions

Step 1

Place chopped broccoli in a large bowl.

Step 2

Sprinkle honey, olive oil, salt and pepper over top. Stir.

Step 3

Cook broccoli in the microwave for four to five minutes, until desired tenderness.

Note

This a great addition to pork chops with hot honey drizzled on top.

Enjoy this easy, delicious dinner!

The spotting of a new predatory hornet in Georgia could mean trouble for Florida’s imperiled honey bees if it spreads further South.

To track the spread of the yellow-legged hornet, scientifically named Vespa velutina, UF/IFAS honey bee experts are working with the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services to spread the word on what residents can do if they see or catch one of these hornets.

Karine Monceau, from Monceau et al. 2014 A yellow-legged hornet, a predator to the honey bee, sits on a plant.

“Honey bees in North America have no natural defenses against the yellow-legged hornet, so keeping this species from making a home in Florida is of the utmost importance to our honey bee populations and thus our food supply,” said Amy Vu, state specialized program extension agent for the University of Florida/IFAS Honey Bee Research and Extension Laboratory.

The Vespa velutina is an invasive hornet that preys on honey bees and honey bee larva. The first United States sighting of the predator, which has already damaged Europe’s bee populations, was last week in Savannah, Georgia, by the Georgia Department of Agriculture after a backyard beekeeper spotted, captured and reported two hornets.

The yellow-legged hornet is smaller, but similar to the Vespa mandarinia, known by its nickname the “murder hornet,” which has a distinct orange mark on its head.

The yellow-legged hornet is best identified by its yellowish-white-colored legs, is about 1.2 centimeters to 3 centimeters long, and has a broad orange-yellow face with large, prominent eyes. The thorax and abdomen are mostly black with a single yellow section near the end of the abdomen, according to UF/IFAS informational documents.

The yellow-legged hornet is often mistaken with the commonly seen European hornet, Vespa crabro, which is not a substantial threat to bees. The European hornet does not have yellow/white legs. European hornet samples should not be submitted, if possible.

To report a suspected yellow-legged hornet email [email protected] or call the FDACS hotline at 1-888-397-1517.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: https://www.mainstreetdailynews.com/local-living/outdoors/uf-ifas-warns-bee-predator-georgia

]]>

Links:

Register Here: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZArdemgrzovEtapijKNqDIVQ7WI5Y3GiQyp

]]>by Kip Tabb

Bees scurry to fill the honeycomb of a frame in Denise Deacon’s hive in Kitty Hawk. Photo: Kip Tabb

KITTY HAWK — Denise Deacon inspects her bees. This year she only has one hive, although in years past she has had more — as many as eight.

She gently pries the lid off and points to the dark brown resin that lines the top of the inside of the hive.

“That’s the propolis,” she says, explaining that it’s resin the bees collect from trees and other plants that they use to weatherproof the hive.

She slides a frame out and looks at it critically. It’s still early in the season for honey production — they’ll get around to that later in the summer. Right now, the bees are concentrating on foraging for food, building the hive and reproduction.

The bees in this frame have been working on the honeycomb for some time and the comb fills almost the entire frame.

She pulls out another frame and in this frame the honeycomb is clearly a work in progress, the comb filling perhaps a third of the frame. Each cell appears to be identical, although they are not. The largest are reserved for the drone bees, smaller ones for workers and the queen bee gets her own shape and size.

The comb, the wax the bees produce to seal the honey in the combs, and the honey are unique to the honeybee. Other bees die off in the winter and emerge as the weather warms. Honeybees stay active in their hive all winter and the honey is their food source.

They produce more honey than they need for the winter, although beekeepers vary in how much honey they’ll harvest. Some, like Deacon, leave enough honey for the hive to get through the winter. Others take all the honey and feed the bees sugar water as a substitute.

“Some people do take off honey and then feed them sugar water, to make it through the winter. They will survive but they won’t be as healthy is my understanding,” she said.

This is Deacon’s 10th year raising her own bees, although the idea had been in the back of her mind since childhood and the onetime attempt by her father.

“In my teens, my father started beekeeping,” she recalled. After a weekend away, “We came back and the house had been broken into and they had kicked over the beehive. He didn’t continue from that point forward. (But) that was just something in the back of my mind that might be a cool thing to do.”

She is a member of the Outer Banks Beekeeper’s Guild, one of the founding members, although she downplays that role.

“In my mind. I may have made phone calls to people to say, ‘Hey, let’s get together and talk about getting a group together,’” she said.

The guild is part of the North Carolina State Beekeepers Association, an amateur beekeeping organization that may be the largest in the country.

“We do have the largest state (bee) association, with nearly 5,000 paid members,” said Dr. David Tarpy, apiculture professor and extension specialist at North Carolina State University. “Compared to even large states like California and Texas (we have) more beekeepers. In Texas and California, those are large-scale commercial guys so they have more colonies but fewer beekeepers.”

There are some large commercial beekeeping operations in the state, but Tarpy, when comparing North Carolinas commercial beekeepers to other states, said they are, “vanishingly small.”

The number could be fewer than a dozen.

Not all the commercial operations take place in the state; they are, in fact, somewhat migratory.

“There are large-scale beekeepers that reside here full time and go out to California every winter for the almonds and up to Maine for the blueberries and things like that,” he said.

David Tarpy of the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology. Photo: NC State

There are 4,000 or so species of bees that live in the United States, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, and the honeybee is not even native to the continent. The first shipment of honeybees arrived in the Virginia Colony in early 1622. By the end of the 17th century, they were part of everyday life, although beeswax was the more valuable commodity at that time.

As an introduced species, there is controversy surrounding honeybees. Deacon pointed out that even her lone hive could have an effect on the local ecology.

“The problem with honeybees, you’re bringing 40,000 insects into this realm of 3 to 5 miles and all these other native bees that are all out there competing for the same plants,” she said.

Tarpy sees the issue of competition with native species as overblown and, perhaps, one that misses more significant questions.

“Whatever competition has happened, it’s been going on for 400-plus years. Ecology responds a lot faster than that,” he said. “There probably has been competition and certainly when beekeepers move their hives into a very fragile area like a desert, they can swamp whatever species are there. So it certainly is an issue and one we need to be cautious about. But is it driving the extinctions of these other bees? I think there are bigger fish to fry for that: pesticides, those kind of things.”

The pollinator population in general is under stress. And, although careless pesticide use does threaten honeybees, the most significant natural peril is the varroa mite.

It is not the mite itself, though, that is the threat, rather it is the disease the mites carry.

“I would say that public enemy No. 1, 2, and 3 are all called the varroa mite,” Tarpy said. “They’re like little vampires, sucking the bees until they’re so anemic that other stressors start to compound. But the biggest thing that we’re actively researching is that it’s not really the varroa mites that kill bees. It’s the viral pathogens that they’re vectoring. They’re like little dirty hypodermic syringe needles.”

There is no easy way to protect bees from varroa mites. The N.C. State Apiculture Program is concentrating on two areas of research: strengthening hives so they can better withstand stress and early detection of infection.

“We offer this service that if you send in your bees, we can … look at all of these different pathogens and see if we can identify if you have an overwhelming pathogen load within the colony,” Tarpy said.

Tarpy’s research is finding ways to identify the strongest queen for a colony. The apiculture lab has developed empirical measurements that can be applied to queen bee health, and Tarpy’s research has shown healthy queens correlate to a healthier hive.

“If you have a bad queen, your ceiling is low. If you have a good queen, your ceiling is high. The queen is this singular thing that beekeepers have control over,” he said.

The work is currently conducted in a dilapidated building on the N.C. State campus.

“Research is being conducted in one of the worst facilities in the University of North Carolina system,” according to the North Carolina State Beekeepers Association’s website. “There is inadequate room for instruction, storage and research … The teaching classroom is in the former kitchen and dining area where long leak stains adorn the sheetrock ceiling. During rain showers, buckets are strategically placed in order to catch rain water that drips through the sheetrock.”

The association lobbied state legislators for funds to replace the building and the North Carolina General Assembly responded in 2019 with $4 million for a new apiculture center.

“We’re on the downhill slope of the design phase, which is the fun part for me because we get to decide what kind of rooms we want, what we’re going to put in it and how we’re going to use it. We’re building this facility exactly the way that it would really work well for apiculture, science and extension. It’s having all the elements that we could ever want,” Tarpy said. Construction is estimated to be completed in August 2024.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Beekeeping in North Carolina largely an amateur endeavor | Coastal Review

]]>To prevent the spread of this destructive hornet throughout the South, UF/IFAS experts are collaborating with the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. They are determined to raise awareness among residents about what they can do if they encounter or capture one of these hornets.

Photos:

Yellow legged hornet: Various views of Vespa velutina. Credit: Georgia Department of Agriculture

Yellow legged hornet: Vespa velutina feeding on nectar. Credit: Karine Monceau, from Monceau et al. 2014

Yellow legged hornet: An invasive yellow-legged hornet. Credit: Allan Smith-Pardo, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org

Yellow legged hornet: An invasive yellow-legged hornet. Credit: Allan Smith-Pardo, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org

Meredith Bauer

University of Florida

Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS)

352-294-3303

]]>

A greater honeyguide feeding on beeswax in Niassa Special Reserve, Mozambique. Credit: Dominic Cram

The honeyguide bird loves beeswax, but needs help breaking open bees’ nests to get it. So it shows a honey badger the way to the nest, who rips it open and together they share the rewards. Or so the story goes.

This Disneyesque tale of two species cooperating for mutual benefit has captivated naturalists for centuries—but is it true?

“While researching honeyguides, we have been guided to bees’ nests by honeyguide birds thousands of times, but none of us have ever seen a bird and a badger interact to find honey,” said Dr. Jessica van der Wal at the University of Cape Town, lead author of the study.

She added, “It’s well-established that honeyguides lead humans to bees’ nests, but evidence for bird and badger cooperation in the literature is patchy—it tends to be old, second-hand accounts of someone saying what their friend saw. So we decided to ask the experts directly.”

In the first large-scale search for evidence of the interaction, a team of young researchers from nine African countries, led by researchers at the University of Cambridge and the University of Cape Town, conducted nearly 400 interviews with honey-hunters across Africa.

Trail camera recording of honey badger eating beeswax and honeycomb after a human harvested a bees’ nest. Credit: Dominic Cram

People in the 11 communities surveyed have searched for wild honey for generations—including with the help of honeyguide birds.

Most communities surveyed were doubtful that honeyguide birds and honey badgers help each other access honey, and the majority (80%) had never seen the two species interact.

But the responses of three communities in Tanzania stood out, where many people said they’d seen honeyguide birds and honey badgers cooperating to get honey and beeswax from bees’ nests. Sightings were most common among the Hadzabe honey-hunters, of which 61% said they had seen the interaction.

“Hadzabe hunter-gatherers quietly move through the landscape while hunting animals with bows and arrows, so are poised to observe badgers and honeyguides interacting without disturbing them. Over half of the hunters reported witnessing these interactions, on a few rare occasions,” said Dr. Brian Wood from the University of California, Los Angeles, who co-authored the study. The report is published in the Journal of Zoology.

A honey badger feeding on honeycomb in Niassa Special Reserve, Mozambique. Credit: Dominic Cram

Examining the evidence

The researchers reconstructed step-by-step, what must happen for honeyguide birds and honey badgers to cooperate in this way. Some steps, such as the bird seeing and approaching the badger, are highly plausible. Others, such as the honeyguide chattering to the badger, and the badger following it to a bees’ nest, remain unclear.

Badgers have poor hearing and bad eyesight, which isn’t ideal for following a chattering honeyguide bird.

The researchers say perhaps only some Tanzanian populations of honey badgers have developed the skills and knowledge needed to cooperate with honeyguide birds, and they pass these skills down from one generation to the next.

It’s also possible, they say, that badgers and birds do cooperate in more places in Africa but simply haven’t been seen.

“The interaction is difficult to observe because of the confounding effect of human presence: observers can’t know for sure who the honeyguide bird is talking to—them or the badger,” said Dr. Dominic Cram in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, a senior author of the study.

He added, “But we have to take these interviews at face value. Three communities report to have seen honeyguide birds and honey badgers interacting, and it’s probably no coincidence that they’re all in Tanzania.”

The authors highlight the need for more scientists to engage with relevant communities and learn from their views and observations, and integrate scientific and cultural knowledge to enrich and accelerate research.

Partner switch?

The greater honeyguide bird, Indicator indicator, is well-known to communities across many African countries, where it has been used for generations to find bees’ nests. Wild honey is a high-energy food that can provide up to 20% of calorie intake—and the wax that hunters share or discard is a valuable food for the honeyguide.

Humans have learned how to read the calls and behavior of the honeyguides to find wild bees’ nests.

“The honeyguides call to the humans, and the humans call back—it’s a kind of conversation as they move through the landscape towards the bees’ nests,” said Dr. Claire Spottiswoode from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, joint senior author of the study.

With our control of fire and tools, humans are useful partners to honeyguides. We can cut down trees, and smoke the bees to subdue them before opening their nests. Honey badgers, Mellivora capensis, are more likely to make the bees angry—and aggressive bees sometimes sting the birds to death.

But honeyguide birds have been around far longer than modern humans, with our mastery of fire and tools.

“Some have speculated that the guiding behavior of honeyguides might have evolved through interactions with honey badgers, but then the birds switched to working with humans when we came on the scene because of our superior skills in subduing bees and accessing bees’ nests. It’s an intriguing idea, but hard to test,” said Spottiswoode.

More information: J. E. M. van der Wal et al, Do honey badgers and greater honeyguide birds cooperate to access bees’ nests? Ecological evidence and honey‐hunter accounts, Journal of Zoology (2023). DOI: 10.1111/jzo.13093

Journal information: Journal of Zoology

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: DOI: 10.1111/jzo.13093

]]>By: Brian Hackney

SEBASTOPOL — The life of a honey bee these days is not so sweet: nearly 50 percent of them died off last year. Take your pick of reasons: Parasites, pesticides, starvation, global warming. To that, Michael Thiele, executive director of Apis Arborea (www.apisarborea.org) in Sonoma County, adds another: housing.

SEBASTOPOL — The life of a honey bee these days is not so sweet: nearly 50 percent of them died off last year. Take your pick of reasons: Parasites, pesticides, starvation, global warming. To that, Michael Thiele, executive director of Apis Arborea (www.apisarborea.org) in Sonoma County, adds another: housing.

For him the problem is boxes.

“Something didn’t feel right,” Thiele said about the usual tools of the beekeeper. “I used that regular bee box that the beekeeper had given to me and there was something about it that made me wonder whether there were maybe other ways of housing bees — other ways of beekeeping.”

That was the beginning of Apis Arborea. At his home near Sebastopol, Thiele met with KPIX to talk about his organization.

“I co-founded a honeybee sanctuary in 2007. It was focused on alternatives to mainstream beekeeping. We decided we wanted to really integrate bio-mimicry and allow bees to live the way they have lived for millions of years — which is in trees,” Thiele explained.

Yes, trees. Not white boxes.

“It’s really challenging to witness that conventional (beekeeping) system,” Thiele continued. “Because, when you look at those boxes, you pretty much realize that they were not designed with the well-being of an animal in mind. The design originates from the 1850s but it’s too cold, it’s too large. An apicultural system that is commercialized and mechanized is not paying attention to the animal but really paying attention to profit and other systems. It’s not at all natural. The annual mortality rate is up to 68 percent of honeybees in boxes. Imagine over 2 million hives every year! And just in the United States! And 68% of them — over 1 million of them — poof! Gone every year. Compare that to honeybees living in the wild and remote areas where the average lifespan is over six years.”

Asked if these data will be heartbreaking for people who keep bees and think they’re doing the right thing, Thiele buried his head in his hands.

“Oh, my. Yes. Heartbreaking. Heartbreaking is exactly the right word.”

Thiele’s organization has designed tree nests which mimic the nest attributes and conditions of wild honeybees.

“We are just bringing that wisdom, that million-year-old wisdom, back into a design that also reflects their needs and that provides conditions for their well-being and survival and health,” he said.

The nests are fashioned from partially hollowed-out cross-sections of logs. The process requires chisels and chainsaws and routers accompanied by plenty of grunting and sweating. The result: a borehole maybe eight inches wide running through the center of a four-foot section of log. These are dragged into the forest, hoisted dozens of feet off the ground and affixed in parallel to trees. Within a couple days, a cloud of bees had buzzed in and set up shop.

Apis Arborea has hung about 150 of the tree nests throughout Northern California and they’re studying the results of the deployment.

“The goal is to go nationwide — actually worldwide,” Thiele said. “This is a large global movement that has really gained traction. We are trying to encourage others to join in and that’s why we’re having workshops and events — to get the idea started that we have to change what we’re doing. We actually have no choice but to change so that, together, we can transform a system that really has no future.”

There was one obvious question for Thiele, who has often laid his hand on top of a thrumming throng of wriggling bees inside the nests: Do you ever get stung?

“Rarely,” he replied. “The more you move with them — with their life gestures — the more you integrate bio-mimicry, the less they’re getting upset because something is moving with them and not against them. It feels like shaking hands with your hearts, with your best friend ever.”

After seeing Thiele’s devotion to bees and their well-being, you wonder if the feeling might be mutual.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: New Age beekeeper looks to the trees for hive health – CBS San Francisco (cbsnews.com)

]]>

Kent Pegorsch of Dancing Bear Apiary recently won an award for his Waupaca Wildflower honey at the Black Jar Honey Tasting Contest, a competition to identify the best tasting honey in the world. James Card Photo

Local honey ranked world class

By James Card

Kent Pegorsch recently won an award that is the equivalent of the Super Bowl of beekeeping.

Pegorsch is the owner of Dancing Bear Apiary. He submitted his Waupaca Wildflower honey to the Black Jar Honey Tasting Contest organized by the Center for Honeybee Research.

The goal of the contest is to identify the best tasting honey in the world. The contest is named “Black Jar” because all of the honey jars are shrouded in a coded black bag so the judges only focus on taste and not color or clarity.

Each year 500 to 1,000 entries are submitted. Out of those, the judges picked 12 winners and the Waupaca honey was among them.

Other winning honeys came from Spain, South Carolina, Hungary, Alaska, Uruguay, Vermont, Netherlands, Kansas and two from Slovakia. The honey from Spain took the grand prize.

The Waupaca honey Pegorsch submitted won in the Medium Amber category. He entered for the first time the year before and he missed being in final 30 entries.

On Sunday, June 4, Pegorsch was working in his bee yard when he heard the news. Stephanie Slater, a fellow Wisconsin beekeeper and friend, was at the completion and called him.

“I just wanted to be the first to congratulate you that you’re in the finals,” Slater said. Then his cell phone reception cut out. He refreshed his phone over and over again.

Pegorsch was working with his son and they discovered the event was being live streamed online except there was no sound as the winners were being announced.

“It was a very intense day. They later confirmed it on Tuesday. I was a little hard to get along with for two days,” said Pegorsch. “This validates that I do know my honey is a really good tasting honey when competing against honeys from all over the world. That’s the most important thing that I get out of this contest and I will definitely be competing in future years,” he said.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Sweet win for Waupaca bees – Waupaca County Post (waupacanow.com)

]]> Zucchini & Tomato Flatbreads

Zucchini & Tomato FlatbreadsBy: Emma Wadel

Ingredients

Ingredients

□ 1 zucchini

□ A small tub of grape tomatoes

□ 1 garlic clove

□ 1 lemon

□ 4oz of ricotta cheese

□ 2 flatbreads (I use the Storefire Naan 2-pack. I have found it holds its structure better than a pure flatbread.)

□ Parsley for garnish (fresh or the dried flakes)

□ Chili flakes (I use red pepper flakes)

□ Honey

□ Olive oil

□ Salt

□ Pepper

Directions

This recipe makes 2 servings.

Step 1

Place a lightly oiled baking sheet on the top rack and preheat the oven to 450 degrees.

Step 2

Step 2

Trim and halve zucchini lengthwise. Thinly slice crosswise into half-moons.

Step 3

Halve tomatoes.

Step 4

Peel and mince or grate garlic. I will normally use a garlic press just to save some time – if you choose that, it will come in a later step.

Step 5

Zest and halve lemon. Quarter one of the halves.

Step 6

Heat a drizzle of olive oil in a large pan over medium-high heat.

Step 7

Add zucchini to hot pan with some salt and pepper and cook, stirring, until lightly browned and softened. It should take around 5-6 minutes.

Step 8

Step 8

In a small bowl, combine tomatoes, garlic (this is the time to use the garlic press, if desired!), and a drizzle of olive oil. Season with salt and pepper.

Step 9

Step 9

In a second small bowl, combine ricotta, half of the lemon zest, ½ teaspoon olive oil, salt, pepper, and lemon juice. I use half the lemon in a lemon squeezer.

Step 10

Once the oven is finished preheating and the prior steps have been completed, remove the baking sheet. Carefully place flatbreads on the prepared sheet.

Step 11

Step 11

Evenly spread flatbreads with the lemon ricotta mix.

Step 12

Top with zucchini and tomatoes. Try to get the tomatoes with the cut sides up.

Step 13

Bake on the top rack until flatbreads are golden brown, about 10-12 minutes.

Step 14

If you’re using fresh parsley, pick the leaves from stems and roughly chop the leaves.

Step 15

Step 15

Once flatbreads are done, garnish with honey, parsley, remaining lemon zest and chili flakes (to taste). Serve with remaining lemon wedges on the side.

Breeding, Bees, and the 4 Ps

Breeding, Bees, and the 4 Ps

Posted by Scott Elliott, ARS Office of Communications in Research and Science

After suffering severe winter losses beginning in 2007, the honey bee population is making a comeback. Still, losses are high, which means beekeepers have to spend a lot of time and money replacing their bees.

Researchers with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Agricultural Research Service (ARS) are responding, by using genetics to selectively breed honey bees to fight the primary perpetrators of the problem – what they call the “four Ps.” According to scientists with the ARS Honey Bee Breeding, Genetics, and Physiology Research (HBBGPR) lab in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the main issues that honey bees contend with are parasites, pathogens, poor nutrition and pesticides.

Honey bees are important to ecosystems and the agriculture system. Honey bees are America’s primary commercial pollinator and more than 100 U.S.-grown crops rely on honey bees and other pollinators. In addition to their important role in maintaining food security, bees provide income to the entire food production industry from beekeepers and farmers to local retailers and international exporters.

The 5-year project at HBBGPR addresses the four Ps through breeding programs that refine selected genetic traits already present in honey bee populations.

“We are breeding honey bees that are more efficient at processing nutrients in their food and are more resistant to pests, pathogens and pesticides,” said Lanie Bilodeau, research leader at HBBGPR. “Developing healthier and more productive honey bee colonies will help ease the effects of disease and climate change, and improve the food supply at local, national and global scales.”

The project is already reaping positive results, including a comprehensive catalog of genetic variation of commercial and research honey bee populations in the country, and nutritional supplements for colony-wide pathogen treatment.

“We think of ourselves as good stewards and shapers of our [honey bee] populations, such that when we make our selection decisions the outcomes are healthier, stronger and more resilient honey bees,” said Arian Avalos, geneticist at HBBGPR.

National Pollinator Week was June19 to June 25. This annual celebration recognizes the important role pollinators play in our food and agricultural systems. Improving the health of honey bees through genomic research and honey bee breeding is just one way USDA is helping protect our nation’s precious pollinators. For more information on USDA’s work to enhance honey bee health, please visit: www.usda.gov/pollinators.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2023/06/20/breeding-bees-and-4-ps

]]>Honey bees aren’t an endangered species; they’re causing chaos

Yes, everyone loves them and keeping them has become a green hobby, but they’d feel differently if a swarm besieged their home

Antonia Hoyle: ‘I frantically vacuumed them up and deposited them outside as fast as they arrived’ CREDIT: Geoff Pugh for The Telegraph

For days, there were only a few, upstairs – blown in through a window, I assumed, by the late spring breeze. But then more came downstairs, gaining ominously in number until one morning three weeks ago, I walked into the living room to find hundreds of the creatures crawling, seemingly lethargic, over the carpet.

“Wasps!” I wailed to my analyst husband, Chris, who like me is 44. I frantically vacuumed them up and deposited them outside as fast as they arrived, until the pest controller arrived at our location home. Pointing at a cloud of black dots dancing around our third-floor chimney, he corrected me: “You’ve got honey bees.”

Being gatecrashed by sugar plum fairies would have been simpler, and less controversial, to navigate. While not illegal, pesticides permitted to treat honey bees in a domestic setting are strictly limited, ethically questionable, and some pest controllers refuse to deploy them.

Short of advising us to stuff the fireplaces they’d been flying in through, and spend hundreds hiring a cherry picker to send someone up to the roof to physically extract them (with no guarantee of success) there was little he could do, the pest control man apologised, letting us know, for what it was worth, that we are far from alone.

This month beekeepers reported an increase in honeybee swarms – which happen when the old queen departs the hive with half the bees to set up a new home – caused by the sudden change in weather after a long, cold spring.

Usually, this split happens in a “staggered manner,” explains Matthew Richardson, president of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, but because of the delay in decent weather “the bees have been queuing up waiting to swarm and they’re all going at once.”

For many, the image might gladden the heart. Chris’s eyes certainly softened when I disclosed the identity of our uninvited guests and our 12-year-old daughter Rosie was delighted: “They’re an endangered species!”

But are they? In recent years, wildlife campaigners have made huge efforts to raise awareness of the importance of bees, of which there are around 270 species in the UK, including 24 species of bumble bees and hundreds of wild solitary bees that nest alone in cavities or underground.

Many are in decline – we have already lost around 13 species, including the short-haired bumblebee, last recorded in 1956, and the great yellow bumblebee in 1974. Another 35 species are currently at risk, with the use of pesticides in farming and destruction of pollen and nectar to feed off largely to blame – the UK has lost 97 per cent of its wildflower meadows since the 1930s.

Concern around honey bees, however, seems to stem from 2007, when an unexplained condition called colony collapse disorder (CCD), in which worker bees in a honey bee colony disappear, was officially recognised. Colony losses were reported in America and Europe and the potential impact on agriculture – according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the global value of global crops pollinated by honey bees in 2005 was estimated at over £150bn – was huge.

Within a decade, the threat of CCD seemingly passed, but our passion for honey bees continued, often in cities where beekeeping has become a fashionable “green” hobby. In 2021 UK Google searches for “urban beekeeping” jumped 21 per cent in a year. Celebrities who keep bees, meanwhile, include David Beckham and Jeremy Clarkson and last month a picture of the Princess of Wales wearing a beekeeper’s suit while tending to a hive in her Norfolk estate was released to mark World Bee Day.

“There’s definitely a popular misconception around bees,” says Andrew Whitehouse of insect conservation charity Buglife, who says honey bees are “not endangered, they’re essentially livestock” and believes misunderstandings began when charities such as his own started to raise awareness of the importance of all pollinating insects around 20 years ago: “Perhaps the conservation organisations didn’t explain things properly and well-meaning people reached for the solution which was to increase the number of honey bees.”

At the same time as charities were starting to promote the importance of “wild pollinators,” he adds, CCD was becoming widely known: “I think the two issues were conflated a bit.”

Because honey bees are good at collecting pollen and returning it straight to their hives, they are less efficient at pollinating some plants than wild bees, with whom they compete for pollen. And honey bee hives are bigger than most……

To read the complete article go to;

Honey bees aren’t an endangered species; they’re causing chaos (telegraph.co.uk)

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Honey bees aren’t an endangered species; they’re causing chaos (telegraph.co.uk)

]]>