BY CHRIS SLAY

A quart of very fresh wildflower honey will taste like a sunny summer day all year long.

A quart of very fresh wildflower honey will taste like a sunny summer day all year long.

During the honey flow period, many established colonies made more honey than they need. In this four-part series, we’ll explore exactly what honey is, what differentiates some honey from others, traditional and modern medical uses, and the rich history humans have with honey as a food source. We’ll also disprove some common misconceptions about honey. Welcome back to the fascinating life cycle of the honey bee.

Honey begins as nectar from flowers. Worker bees collect nectar and pollen for food. The nectar that isn’t immediately consumed is stored in bees’ honey bellies and taken back to the hive. Honey bees’ salivary enzymes and proteins break down the nectar’s complex sucrose and starches into simple, more quickly digested sugars — glucose and fructose.

Because wild yeasts and bacteria can easily live on nectar, robbing its nutrients, honey bees reduce the nectar’s water content in two astonishing ways. First, they repeatedly regurgitate the nectar into their mandibles to create bubbles that provide a large surface area for water to evaporate. Second, after storing the partially dehydrated solution in open wax cells, groups of workers will constantly fan their wings, producing heat and airflow to reduce the water content even further. After the solution lowers to a water content of 18% to 15.5%, bees cap the cells with wax.

The nectar is now beyond the saturation point of water. This means there is far more sugar dissolved in what little water remains than ever could be dissolved in an equivalent volume of water.

For example, it’s impossible to dissolve one cup of sugar in seven teaspoons of water. This is honey.

Honey’s supersaturation of sugar is incredibly stable on molecular and chemical levels. Yeasts and bacteria are deterred from living on honey while in the capped cells, which ensures a very fresh and untainted food source.

The type of honey a colony produces depends entirely on the nectar’s primary source. Wildflower, the most abundant type of honey, is a combination of all of the thousands of different flowers from which the bees forage. Wildflower honey is typically light to dark amber in color and can have a very complex, multi-faceted taste. Other local nectar sources, such as basswood, tulip poplar, and sourwood trees, produce a much lighter-tasting, grassy-golden honey. Regardless of what the label says, no one knows what other flowers’ nectars are present without microscopically identifying the unique pollen cells in honey. Bees don’t discriminate.

At retail, honey is offered in many forms, but it’s either raw or processed. Most commercially produced honey is pasteurized, which ensures bacterial decontamination that may occur after uncapping the cells for extraction and the packaging process. Raising the temperature of honey above 104F also diminishes many of the unique qualities of honey. If you’ve ever had milk fresh from the cow, you understand. Commercial honey may also contain additives like high-fructose corn syrup or artificial coloring.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: All about honey – part 1 | Community News | thetomahawk.com

]]>

Propolis is a sticky resinous substance found in bee hives.

Beekeepers look to untapped potential of propolis, or ‘bee glue’, as alternative revenue stream

A by-product of honey production largely discarded in Australia could provide an alternative income source for beekeepers across the country.

Hidden within the walls of their hives, bees blend up a unique mix of materials that scientists believe holds untapped potential in Australia.

Propolis is a sticky, resinous substance that’s sometimes referred to as “bee glue”.

Bees use propolis as a powerful sterilising agent as well as to seal gaps in their hives against predators and the elements.

‘Propolis is used by the bees because they don’t have an immune system,” Queensland beekeeper Murray Arkadieff said.

“Bees forage within a 7 kilometre radius of the beehive, so that means they cover about 210km²,” he said.

Murray Arkadieff has been a beekeeper his entire life.

Mr Arkadieff said the bees were able to look throughout that 210km² and search for parts of plants that could be used to polish their hives.

The bees not only forage for nectar and pollen, but also for other parts of the natural environment such as sap or bark.

“They bring that back to the beehive and they can mix it all together and it turns it into a really strong antimicrobial, anti-fungal, antiviral and antibacterial material, which they polish their entire hive with,” he said.

Propolis and its medicinal wonders

Propolis also has benefits for people and is used in many different countries in medicines, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

“Propolis contains high polyphenolic compounds,” organic chemist from the University of the Sunshine Coast Trong Tran said.

“Australian propolis is very diverse and it also shows very comparable, even higher antioxidant activities compared with the other well-known propolis in the world, Dr Tran said”

Despite being part of a well-established industry elsewhere, in Australia there isn’t large-scale commercial propolis harvesting and processing.

“We’ve always mainly been focused on liquid honey production,” Mr Arkadieff said.

“It’s not something that Australians have looked into in a massive way, which is why it’s such an exciting opportunity for the industry.”

Peter Brooks is part of the research team from the University of the Sunshine Coast that has been part of the Australian Propolis Project, an initiative supported by the federal government’s Agrifutures organisation.

“When we started talking to beekeepers about what they were interested in they were saying: ‘Well this propolis product that they throw out, it’s got a lot of value, so how could we use that in some of our research?” Dr Brooks said.

Samples of propolis were collected from different areas around the country and were sent to the lab to be analysed.

“Like everything, if you’re throwing something away that you could be making money for — it could be a new source of income.”

To begin with, scientists needed to ensure that Australian propolis was valuable, given its specific properties were largely unknown.

A buzzing opportunity for beekeepers

Hive and Wellness Australia, formerly known as Capilano, asked its 1,200 beekeepers nationally to consider participating in a trial collection of propolis.

Samples collected from all over the country were sent to the University of the Sunshine Coast for analysis.

“Of those samples that came back I think there was around 55 per cent that showed high antioxidant compounds,” said Jessica Berry, an industry liaison officer with Hive and Wellness Australia.

Dr Tran leads the research team, which is focused on finding out which samples hold the higher antioxidant value, and why.

He thinks one reason might be that about 80 per cent of Australia’s plants are endemic, and so aren’t found anywhere else.

“So we can expect that Australian propolis is unique to other areas in the world,” he said.

The complete article can be found at; https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-23/australian-beehives-propolis-alternative-revenue-for-beekeepers/102625256o

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-23/australian-beehives-propolis-alternative-revenue-for-beekeepers/102625256o

]]>The sweet stuff can help with burns, coughs, anxiety and more

By Alison Gwinn,

AARP

Photo by Daily Slowdown on Unsplash

Honey’s benefits have been touted since antiquity — and it turns out the ancient Greeks and Romans were onto something: Honey really can hit the sweet spot when it comes to our health.

Though honey — a sweet, sticky liquid made by honeybees from flower nectar — is technically a sugar, “it’s also really rich in a lot of different bioactive substances,” says Mayo Clinic registered dietitian (and hobbyist beekeeper) Joy Heimgartner. Those include a range of good-for-you minerals, probiotics, enzymes, antioxidants and other phytochemicals.

There are four common types of honey: Raw honey is defined by the National Honey Board as “honey as it exists in the beehive or as obtained by extraction, settling or straining without adding heat.” Manuka honey, produced from the flowers of manuka trees, is known for its unique antibacterial properties, attributed to a compound called methylglyoxal, says Jordan Hill, lead registered dietitian for Top Nutrition Coaching.

Organic honey is produced without the use of synthetic chemicals, pesticides or GMOs. And locally produced honey has been reported to provide relief from seasonal allergies to local pollen, though scientific evidence to support that claim is limited, says Hill.

According to Hill, honey can be substituted for sugar in recipes, but remember: It has a distinctive flavor (which varies depending on the source flowers); it’s sweeter than sugar (the general rule of thumb is to use ¾ to 1 cup of honey for every 1 cup of sugar); it’s a liquid, so you may need to cut back on other liquids or slightly increase the dry ingredients in a recipe; and it browns more quickly than sugar (so reduce the oven temperature by 25°F).

But whatever way you use honey — in a recipe or as a condiment — always keep in mind that it is a sweetener. “Honey is a supersaturated sugar solution, and we should limit added sugars of all types,” says Heimgartner. Still, “if you’re looking for a sweetener that has more to offer, honey is fantastic.” Here are six reasons why.

- Honey doesn’t raise your blood sugar as rapidly as white sugar

“Honey is metabolized differently from white sugar and produces less of a sugar spike,” says registered dietitian and nutritionist Dawn Jackson Blatner, author of The Flexitarian Diet. “Research suggests that honey may enhance insulin sensitivity and may support the pancreas, the organ that produces insulin.” A 2018 review of preliminary studies points to honey’s “hypoglycemic effect” and use as a “novel antidiabetic agent that might be of potential significance for the management of diabetes and its complications.”

And a 2022 study out of the University of Toronto found that honey improves important measures of cardiometabolic health, including blood sugar, cholesterol and triglyceride levels, especially if the honey is raw and from a single source.

- Honey can help with wound or burn therapy

“Honey has been used for wound healing for centuries, and certain types of honey, like medical-grade honey, have shown potential in wound management due to their antimicrobial properties and ability to promote healing,” says Hill, who nonetheless advises consulting health care professionals for appropriate wound care. Heimgartner, a board-certified oncology specialist, says, “There’s actually a lot of evidence that using honey during oral cancer radiation treatment helps to prevent some of the nasty side effects of mucositis,” or inflammation of the mouth.

How does it work? “Research suggests that honey prevents or controls the growth of bacteria on the wound, helps to slough off dead tissue and microorganisms, and transports oxygen and nutrients into a wound for quicker healing,” says Blatner.

Native plants and naturalistic perennials attract bees and other pollinators.

Create Your Own Pollinator Garden

If you want to create your own pollinator garden for bees to forage in, consider these tips from Emily Erickson, postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis, department of evolution and ecology.

- Opt for native plants or naturalistic perennials.

- Choose plants of varying colors, shapes and bloom times so you can support a variety of pollinators throughout the season.

- Avoid double-flowered varieties (those with extra petals) or plants that look drastically different from their wild relatives.

- Avoid pesticides.

- Leave areas in your yard that can serve as nesting habitats, such patches of bare soil, brush, twigs or woody stems, where many native pollinators make their homes.

- Which plants are right for you depends on your location and climate, so ask your local nursery for advice — or simply walk through a nursery and notice which plants seem to attract pollinators.

- Honey is rich in polyphenols, including flavonoids

Why does that matter? Because those two substances have both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, meaning they protect our bodies against oxidative stress, which can manifest as cancer, heart disease or other diseases. But Hill cautions that the polyphenols in honeys can vary significantly, depending on the type of honey and its floral source.

- Honey can be an effective cough suppressant

A 2020 meta-analysis found that honey provides a widely available and inexpensive alternative to antibiotics in controlling cough frequency and severity, though it concluded that further studies were needed. “It is believed that honey’s thick texture and possible antioxidant and antimicrobial properties may provide relief for cough symptoms,” Hill says, but she adds the caveat that honey should never be given to infants under 1 year of age due to a risk of botulism.

- Honey may provide antidepressant or anti-anxiety benefits.

“Research suggests that polyphenol compounds in honey such as apigenin, caffeic acid, chrysin, ellagic acid and quercetin support a healthy nervous system, which may enhance memory and support mood,” says Blatner. Though more study is needed, a 2014 review of research says that one established nootropic (or cognitive-enhancing) property of honey “is that it assists the building and development of the entire central nervous system, particularly among newborn babies and preschool-age children, which leads to the improvement of memory and growth, a reduction of anxiety, and the enhancement of intellectual performance later in life.”

- Honey may support a healthy gut

Early research indicates that “honey has an extra-special ability to support a healthy gut microbiome because it contains both probiotics, or good bacteria, and prebiotic properties, which help good bacteria thrive,” says Blatner, though the evidence is limited. A 2022 paper funded by the National Institute of Health, Malaysia, concluded that “honey bees and honey, which have the potential to be good sources of probiotics and prebiotics, need to be given greater attention and more in-depth research so they can be taken to the next level.”

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: https://www.aarp.org/health/healthy-living/info-2023/honey-health-benefits.html

]]> Fresh Broccoli with Honey

Fresh Broccoli with HoneyBy: Fay Jarrett

Ingredients

□ 4 cups chopped broccoli

□ ¼ cup honey

□ 1 tbsp olive oil (tuscan herb was used this time)

□ ½ tsp pepper

□ ½ tsp salt

Directions

Step 1

Place chopped broccoli in a large bowl.

Step 2

Sprinkle honey, olive oil, salt and pepper over top. Stir.

Step 3

Cook broccoli in the microwave for four to five minutes, until desired tenderness.

Note

This a great addition to pork chops with hot honey drizzled on top.

Enjoy this easy, delicious dinner!

By: Brian Hackney

SEBASTOPOL — The life of a honey bee these days is not so sweet: nearly 50 percent of them died off last year. Take your pick of reasons: Parasites, pesticides, starvation, global warming. To that, Michael Thiele, executive director of Apis Arborea (www.apisarborea.org) in Sonoma County, adds another: housing.

SEBASTOPOL — The life of a honey bee these days is not so sweet: nearly 50 percent of them died off last year. Take your pick of reasons: Parasites, pesticides, starvation, global warming. To that, Michael Thiele, executive director of Apis Arborea (www.apisarborea.org) in Sonoma County, adds another: housing.

For him the problem is boxes.

“Something didn’t feel right,” Thiele said about the usual tools of the beekeeper. “I used that regular bee box that the beekeeper had given to me and there was something about it that made me wonder whether there were maybe other ways of housing bees — other ways of beekeeping.”

That was the beginning of Apis Arborea. At his home near Sebastopol, Thiele met with KPIX to talk about his organization.

“I co-founded a honeybee sanctuary in 2007. It was focused on alternatives to mainstream beekeeping. We decided we wanted to really integrate bio-mimicry and allow bees to live the way they have lived for millions of years — which is in trees,” Thiele explained.

Yes, trees. Not white boxes.

“It’s really challenging to witness that conventional (beekeeping) system,” Thiele continued. “Because, when you look at those boxes, you pretty much realize that they were not designed with the well-being of an animal in mind. The design originates from the 1850s but it’s too cold, it’s too large. An apicultural system that is commercialized and mechanized is not paying attention to the animal but really paying attention to profit and other systems. It’s not at all natural. The annual mortality rate is up to 68 percent of honeybees in boxes. Imagine over 2 million hives every year! And just in the United States! And 68% of them — over 1 million of them — poof! Gone every year. Compare that to honeybees living in the wild and remote areas where the average lifespan is over six years.”

Asked if these data will be heartbreaking for people who keep bees and think they’re doing the right thing, Thiele buried his head in his hands.

“Oh, my. Yes. Heartbreaking. Heartbreaking is exactly the right word.”

Thiele’s organization has designed tree nests which mimic the nest attributes and conditions of wild honeybees.

“We are just bringing that wisdom, that million-year-old wisdom, back into a design that also reflects their needs and that provides conditions for their well-being and survival and health,” he said.

The nests are fashioned from partially hollowed-out cross-sections of logs. The process requires chisels and chainsaws and routers accompanied by plenty of grunting and sweating. The result: a borehole maybe eight inches wide running through the center of a four-foot section of log. These are dragged into the forest, hoisted dozens of feet off the ground and affixed in parallel to trees. Within a couple days, a cloud of bees had buzzed in and set up shop.

Apis Arborea has hung about 150 of the tree nests throughout Northern California and they’re studying the results of the deployment.

“The goal is to go nationwide — actually worldwide,” Thiele said. “This is a large global movement that has really gained traction. We are trying to encourage others to join in and that’s why we’re having workshops and events — to get the idea started that we have to change what we’re doing. We actually have no choice but to change so that, together, we can transform a system that really has no future.”

There was one obvious question for Thiele, who has often laid his hand on top of a thrumming throng of wriggling bees inside the nests: Do you ever get stung?

“Rarely,” he replied. “The more you move with them — with their life gestures — the more you integrate bio-mimicry, the less they’re getting upset because something is moving with them and not against them. It feels like shaking hands with your hearts, with your best friend ever.”

After seeing Thiele’s devotion to bees and their well-being, you wonder if the feeling might be mutual.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: New Age beekeeper looks to the trees for hive health – CBS San Francisco (cbsnews.com)

]]>

Kent Pegorsch of Dancing Bear Apiary recently won an award for his Waupaca Wildflower honey at the Black Jar Honey Tasting Contest, a competition to identify the best tasting honey in the world. James Card Photo

Local honey ranked world class

By James Card

Kent Pegorsch recently won an award that is the equivalent of the Super Bowl of beekeeping.

Pegorsch is the owner of Dancing Bear Apiary. He submitted his Waupaca Wildflower honey to the Black Jar Honey Tasting Contest organized by the Center for Honeybee Research.

The goal of the contest is to identify the best tasting honey in the world. The contest is named “Black Jar” because all of the honey jars are shrouded in a coded black bag so the judges only focus on taste and not color or clarity.

Each year 500 to 1,000 entries are submitted. Out of those, the judges picked 12 winners and the Waupaca honey was among them.

Other winning honeys came from Spain, South Carolina, Hungary, Alaska, Uruguay, Vermont, Netherlands, Kansas and two from Slovakia. The honey from Spain took the grand prize.

The Waupaca honey Pegorsch submitted won in the Medium Amber category. He entered for the first time the year before and he missed being in final 30 entries.

On Sunday, June 4, Pegorsch was working in his bee yard when he heard the news. Stephanie Slater, a fellow Wisconsin beekeeper and friend, was at the completion and called him.

“I just wanted to be the first to congratulate you that you’re in the finals,” Slater said. Then his cell phone reception cut out. He refreshed his phone over and over again.

Pegorsch was working with his son and they discovered the event was being live streamed online except there was no sound as the winners were being announced.

“It was a very intense day. They later confirmed it on Tuesday. I was a little hard to get along with for two days,” said Pegorsch. “This validates that I do know my honey is a really good tasting honey when competing against honeys from all over the world. That’s the most important thing that I get out of this contest and I will definitely be competing in future years,” he said.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Sweet win for Waupaca bees – Waupaca County Post (waupacanow.com)

]]> Zucchini & Tomato Flatbreads

Zucchini & Tomato FlatbreadsBy: Emma Wadel

Ingredients

Ingredients

□ 1 zucchini

□ A small tub of grape tomatoes

□ 1 garlic clove

□ 1 lemon

□ 4oz of ricotta cheese

□ 2 flatbreads (I use the Storefire Naan 2-pack. I have found it holds its structure better than a pure flatbread.)

□ Parsley for garnish (fresh or the dried flakes)

□ Chili flakes (I use red pepper flakes)

□ Honey

□ Olive oil

□ Salt

□ Pepper

Directions

This recipe makes 2 servings.

Step 1

Place a lightly oiled baking sheet on the top rack and preheat the oven to 450 degrees.

Step 2

Step 2

Trim and halve zucchini lengthwise. Thinly slice crosswise into half-moons.

Step 3

Halve tomatoes.

Step 4

Peel and mince or grate garlic. I will normally use a garlic press just to save some time – if you choose that, it will come in a later step.

Step 5

Zest and halve lemon. Quarter one of the halves.

Step 6

Heat a drizzle of olive oil in a large pan over medium-high heat.

Step 7

Add zucchini to hot pan with some salt and pepper and cook, stirring, until lightly browned and softened. It should take around 5-6 minutes.

Step 8

Step 8

In a small bowl, combine tomatoes, garlic (this is the time to use the garlic press, if desired!), and a drizzle of olive oil. Season with salt and pepper.

Step 9

Step 9

In a second small bowl, combine ricotta, half of the lemon zest, ½ teaspoon olive oil, salt, pepper, and lemon juice. I use half the lemon in a lemon squeezer.

Step 10

Once the oven is finished preheating and the prior steps have been completed, remove the baking sheet. Carefully place flatbreads on the prepared sheet.

Step 11

Step 11

Evenly spread flatbreads with the lemon ricotta mix.

Step 12

Top with zucchini and tomatoes. Try to get the tomatoes with the cut sides up.

Step 13

Bake on the top rack until flatbreads are golden brown, about 10-12 minutes.

Step 14

If you’re using fresh parsley, pick the leaves from stems and roughly chop the leaves.

Step 15

Step 15

Once flatbreads are done, garnish with honey, parsley, remaining lemon zest and chili flakes (to taste). Serve with remaining lemon wedges on the side.

Honey bees aren’t an endangered species; they’re causing chaos

Yes, everyone loves them and keeping them has become a green hobby, but they’d feel differently if a swarm besieged their home

Antonia Hoyle: ‘I frantically vacuumed them up and deposited them outside as fast as they arrived’ CREDIT: Geoff Pugh for The Telegraph

For days, there were only a few, upstairs – blown in through a window, I assumed, by the late spring breeze. But then more came downstairs, gaining ominously in number until one morning three weeks ago, I walked into the living room to find hundreds of the creatures crawling, seemingly lethargic, over the carpet.

“Wasps!” I wailed to my analyst husband, Chris, who like me is 44. I frantically vacuumed them up and deposited them outside as fast as they arrived, until the pest controller arrived at our location home. Pointing at a cloud of black dots dancing around our third-floor chimney, he corrected me: “You’ve got honey bees.”

Being gatecrashed by sugar plum fairies would have been simpler, and less controversial, to navigate. While not illegal, pesticides permitted to treat honey bees in a domestic setting are strictly limited, ethically questionable, and some pest controllers refuse to deploy them.

Short of advising us to stuff the fireplaces they’d been flying in through, and spend hundreds hiring a cherry picker to send someone up to the roof to physically extract them (with no guarantee of success) there was little he could do, the pest control man apologised, letting us know, for what it was worth, that we are far from alone.

This month beekeepers reported an increase in honeybee swarms – which happen when the old queen departs the hive with half the bees to set up a new home – caused by the sudden change in weather after a long, cold spring.

Usually, this split happens in a “staggered manner,” explains Matthew Richardson, president of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, but because of the delay in decent weather “the bees have been queuing up waiting to swarm and they’re all going at once.”

For many, the image might gladden the heart. Chris’s eyes certainly softened when I disclosed the identity of our uninvited guests and our 12-year-old daughter Rosie was delighted: “They’re an endangered species!”

But are they? In recent years, wildlife campaigners have made huge efforts to raise awareness of the importance of bees, of which there are around 270 species in the UK, including 24 species of bumble bees and hundreds of wild solitary bees that nest alone in cavities or underground.

Many are in decline – we have already lost around 13 species, including the short-haired bumblebee, last recorded in 1956, and the great yellow bumblebee in 1974. Another 35 species are currently at risk, with the use of pesticides in farming and destruction of pollen and nectar to feed off largely to blame – the UK has lost 97 per cent of its wildflower meadows since the 1930s.

Concern around honey bees, however, seems to stem from 2007, when an unexplained condition called colony collapse disorder (CCD), in which worker bees in a honey bee colony disappear, was officially recognised. Colony losses were reported in America and Europe and the potential impact on agriculture – according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the global value of global crops pollinated by honey bees in 2005 was estimated at over £150bn – was huge.

Within a decade, the threat of CCD seemingly passed, but our passion for honey bees continued, often in cities where beekeeping has become a fashionable “green” hobby. In 2021 UK Google searches for “urban beekeeping” jumped 21 per cent in a year. Celebrities who keep bees, meanwhile, include David Beckham and Jeremy Clarkson and last month a picture of the Princess of Wales wearing a beekeeper’s suit while tending to a hive in her Norfolk estate was released to mark World Bee Day.

“There’s definitely a popular misconception around bees,” says Andrew Whitehouse of insect conservation charity Buglife, who says honey bees are “not endangered, they’re essentially livestock” and believes misunderstandings began when charities such as his own started to raise awareness of the importance of all pollinating insects around 20 years ago: “Perhaps the conservation organisations didn’t explain things properly and well-meaning people reached for the solution which was to increase the number of honey bees.”

At the same time as charities were starting to promote the importance of “wild pollinators,” he adds, CCD was becoming widely known: “I think the two issues were conflated a bit.”

Because honey bees are good at collecting pollen and returning it straight to their hives, they are less efficient at pollinating some plants than wild bees, with whom they compete for pollen. And honey bee hives are bigger than most……

To read the complete article go to;

Honey bees aren’t an endangered species; they’re causing chaos (telegraph.co.uk)

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Honey bees aren’t an endangered species; they’re causing chaos (telegraph.co.uk)

]]>

With summer just around the corner, optimal temperature for the bees is about 95 degrees, any hotter and the bees will begin to exhibit stress have difficultly of surviving.

Beekeeper Dave Sharpless went to check on one of his beehives during this June 2019 day in Henderson only to find empty, melted hives.

The days of triple-degree heat during the summer months in Southern Nevada are extreme enough to drive some bee colonies from their hives, leaving behind a melted, sticky mess, he said.

Fall and winter are typically the most precarious time for hives, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, but Sharpless said comparably milder winters in the region are easier for them to get through. The real danger is summer heat even if bees have plenty of water and food.

“We lose more hives in the summer, it’s so extreme,” Sharpless said.

Sharpless has been keeping bees for 10 years and running the bee removal company LV Bees for six years. Instead of exterminating bees, he and partner Destry Myers move hives from customers’ properties to wooden structures in one of several Henderson fields, where he cares for them.

The incident four years ago was the first time they noticed the empty hives.

Sharpless began narrowing down what had caused them to flee. Colony Collapse Disorder wasn’t to blame, because instead of leaving the queen and a handful of nurse bees the colonies had completely abandoned their hive.

If pesticides or illness were the cause, dead bees would have been left behind.

“For most of those hives, even in full sun, 112 degrees is not a problem,” Sharpless said. “When it gets to be 117, 118, that’s when they say, ‘Nah, we can’t handle it.’ The honey starts to drip down on them and they say ‘Forget it, we’re out of here.’”

The following summer, Sharpless provided a closer water source that should have met their cooling and drinking needs and laid down bee-safe fire ant traps, but the exact same thing happened.

It only stopped in 2021, when he topped all of his boxes with 1-inch slabs of insulation foam, cutting down the heat and providing some extra shade.

To make matters stranger, it only happened to his hives in Southern Nevada.

“I have hives out in Arizona, out in the open like this, that don’t need the panels,” he said. “You’d think Northern Arizona gets just as hot as here. I have land in Moapa, and I don’t cover those either.”

Bees aren’t unequipped to deal with heat. In summer, they regulate the temperature inside their hives by collecting water, spreading droplets throughout the hive and fanning them with their wings to air condition the structures, he said.

Allen Gibbs, a life sciences professor and insect physiology expert at UNLV, said desert bee varieties should know how to weather the hottest temperatures. Some fly around with body temperatures of more than 120 degrees, he said.

“For the native bees, these are conditions they’re used to,” Gibbs said. “It’s kind of warm here for honeybees, but (native ones) do OK.”

He said the decades-long drought plaguing the area is a bigger problem for Southern Nevada bees than the heat itself.

“The hotter it gets, the faster they lose water,” he said. “That’s true for any insect.”

For Sharpless, business picks up fast in March and stays busy until the end of June. April and May are the busiest because colonies are growing their numbers and new swarms are splitting off to start their own colonies.

“I get calls two times a day from people like that. ‘I’ve got them under my composting!’ ‘I’ve got them under my shed!’ ‘I’ve got them in my roof,’” Sharpless said. “I’m like yeah, you’re not the only one. We’re booked.”

Sharpless said wild bees typically have a sense for where to build their hives to escape the heat, even in early spring. They’ll seek shade and enclosed spaces like irrigation valve boxes and any gaps inside unsuspecting Nevadans’ walls.

One recent customer, a woman who’d never encountered a hive in her 13 years in Las Vegas, realized a colony had made a home not only on, but in, the decking under her balcony, he said.

Their queen found her way into the interior wall through a hole left over from a speaker installation and the whole colony followed, making themselves cozy in the shaded, enclosed, insulated space.

Sharpless and Myers captured the colony and moved them to a box in the Henderson field.

Las Vegas isn’t the lone area of bee meltdowns as the earth’s temperature continues to rise.

In Australia, homeowners found honey leaking out of her wall and pooling onto the floor, according to 2020 report from ABC Radio in Perth. The homeowners found a melting hive weighing about 220 pounds inside an enclosed, unused chimney.

A Canadian bee researcher also in 2020 raised the alarm after discovering huge numbers of drones, or male honey bees, died of shock from heat stress.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Summer heat a buzzkill for Southern Nevada’s bees – Las Vegas Sun Newspaper

]]>By: Shana Archibald

Ingredients

Ingredients

□ ½ cup butter (softened)

□ ⅔ cup honey

□ 2 eggs

□ 1 tablespoon lemon juice

□ ¼ teaspoon salt

□ Zest from half a lemon

□ ¾ cup flour

□ ¾ cup raspberries (or mixed berry blend,

which is what I used)

Glaze Ingredients

□ ¾ to 1 cup powdered sugar

□ 1 teaspoon raspberry jam

□ 1 tablespoon lemon juice

Directions

Step 1

Preheat oven to 350°F.

Step 2

Prepare an 8×8 square pan by spraying it with non-stick spray (or lining it with parchment paper).

Step 3

In a large bowl, combine butter, eggs, honey, lemon juice, salt and zest. Mix by hand or hand mixer.

Step 4

Add flour and mix until just combined.

Step 5

Add fresh raspberries (or mixed berries) and stir in by hand.

Step 6

Step 6

Pour into prepared pan and spread into an even layer.

Step 7

Bake for around 25 minutes or until edges are brown and the middle is set. Do not over bake! You want the texture to be like a brownie.

Step 8

Let it cool.

Step 9

While the bars are cooling, combine the glaze ingredients and whisk together.

Step 10

Pour it over the cooled bars and spread out into an even layer on the top. Let the glaze set for at least 20 minutes.

Step 11

Cut into squares and serve.

Store at room temperature or in the refrigerator in an air tight container. Enjoy!

]]>Intellectual Property Office rules that New Zealand beekeepers’ attempt to stop Australian producers using the name did not meet necessary requirements

Tess McClure in Auckland

New Zealand honey producers have lost their latest battle to trademark mānuka honey, the latest blow in a years-long fight to stop Australian beekeepers using the lucrative name.

The Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand ruled on Monday that New Zealand mānuka beekeepers’ attempt for a trademark did not meet necessary requirements, and the term mānuka was descriptive.

Mānuka refers to a white flowered tree that grows in both New Zealand and Australia – although it is more widely known as “tea tree” in Australia. The bees that browse its tiny pale blooms produce a kind of honey known for antibacterial and supposed health properties – and which fetches a significant price markup on the international market as a result.

At the highest concentrations, some New Zealand batches have fetched up to NZ$2,000 to $5,000 for a 250g jar at luxury stores overseas. The lucrative nature of the product has been responsible for outbreaks of crime in New Zealand, with fierce competition over access to mānuka forests spurring mass poisonings of bees, thefts, vandalism and beatings.

For more than a decade, however, the two countries have been at loggerheads over the use of the mānuka name – a Māori word, which New Zealand argues is an indigenous treasure, uniquely associated with its own honey production. Pita Tipene, Chair of the Manuka Charitable Trust, said the decision was “disappointing in so many ways”. He said the trust would pause to regroup, before continuing its battle.

“If anything, it has made us more determined to protect what is ours on behalf of all New Zealanders and consumers who value authenticity,” he said.

“Our role as kaitiaki [guardians] to protect the mana [dignity] and value of our taonga [treasured] species, including mānuka on behalf of all New Zealanders is not contestable.”

Australian industry players welcomed the decision as a “commonsense outcome” and issued a press release saying they had plans to grow international sales in response to rising demand.

Australian Manuka Honey Association chairman Ben McKee said he was “delighted” by the ruling.

“Our product has a long history of being recognised as manuka honey, it is produced like the NZ product is, and it also offers the sought-after antimicrobial properties that consumers around the world value so highly,” he said.

New Zealand producers first tried to trademark the term in 2015.

The Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand called the fight “a trans-Tasman tussle of extraordinary proportions” and said in its ruling that it was “one of the most complex and long-running proceedings to have come before the Intellectual Property Office”. The latest decision follows a similar 2021 ruling from the UK to not grant trademark status.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: New Zealand loses fight with Australia over mānuka honey trademark | New Zealand | The Guardian

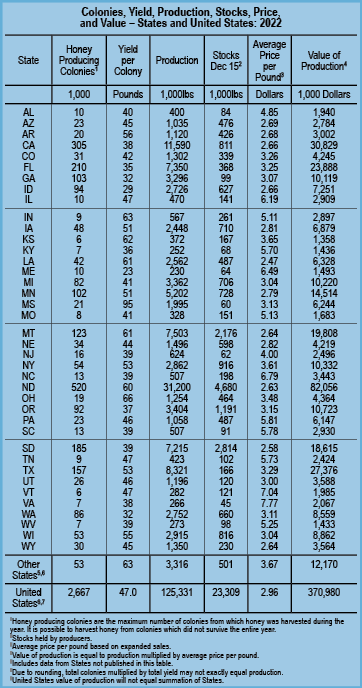

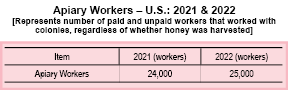

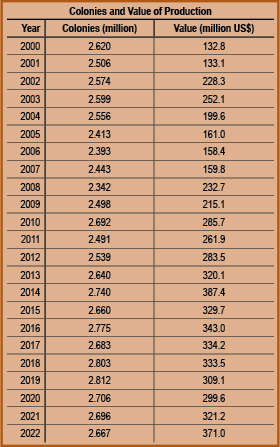

]]>Released March 17, 2023, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

United States Honey Production Down One Percent in 2022

United States Honey Production Down One Percent in 2022

United States honey production in 2022 totaled 125 million pounds, down one percent from 2021. There were 2.67 million colonies producing honey in 2022, down one percent from 2021. Yield per colony averaged 47.0 pounds, unchanged from 2021. Colonies which produced honey in more than one state were counted in each state where the honey was produced. Therefore, the United States level yield per colony may be understated, but total production would not be impacted. Colonies were not included if honey was not harvested. Producer honey stocks were 23.3 million pounds on December 15, 2022, down one percent from a year earlier. Stocks held by producers exclude those held under the commodity loan program, which are entered separately.

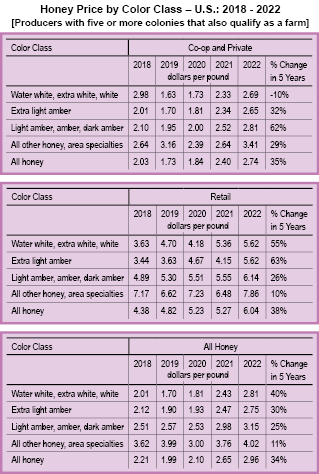

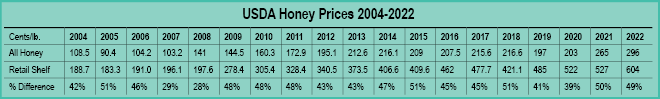

Honey Prices Up 12 Percent in 2022

United States honey prices increased 12 percent during 2022 to $2.96 per pound, compared to $2.65 per pound in 2021. United States and state level prices reflect the portions of honey sold through cooperatives, private and retail channels. Prices for each color class are derived by weighing the quantities sold for each marketing channel. Prices for the 2021 crop reflect honey sold in 2021 and 2022. Some 2021 crop honey was sold in 2022, which caused some revisions to the 2021 crop prices.

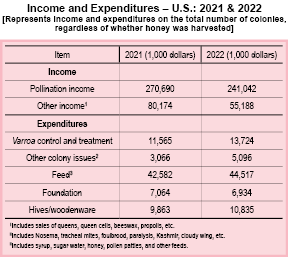

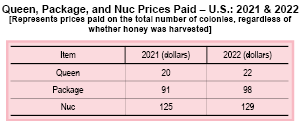

Price Paid for Queens, Packages, Nucs was 22 Dollars in 2022

The average prices paid in 2022 for honey bee queens, packages and nucs were $22, $98 and $129, respectively. Pollination income for 2022 was $241 million, down 11 percent from 2021. Other income from honey bees in 2022 was $55.2 million, down 31 percent from 2021.

Released August 1, 2022, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Released August 1, 2022, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

January 1, 2021 – Some History

Honey Bee Colonies Down One Percent for Operations with Five or More colonies

Honey bee colonies for operations with five or more colonies in the United States on January 1, 2022 totaled 2.88 million colonies, down one percent from January 1, 2021. The number of colonies in the United States on April 1, 2022, was 2.92 million colonies. During 2021, honey bee colonies on January 1, April 1, July 1 and October 1 were 2.90 million, 2.83 million, 3.17 million and 3.09 million colonies, respectively.

Honey bee colonies lost for operations with five or more colonies from January through March 2022, was 331,780 colonies, or 12 percent. The number of colonies lost during the quarter of April through June 2022, was 282,630 colonies, or 10 percent. During the quarter of January through March 2021, colonies lost totaled 464,640 colonies, or 16 percent, the highest number lost of any quarter surveyed in 2021. The quarter surveyed in 2021 with the lowest number of colonies lost was July through September, with 295,660 colonies lost, or nine percent.

Honey bee colonies added for operations with five or more colonies from January through March 2022 was 367,890 colonies. The number of colonies added during the quarter of April through June 2022 was 589,630. During the quarter of April through June 2021, the number of colonies added were 665,730 colonies, the highest number of honey bee colonies added for any quarter surveyed in 2021. The quarter of October through December 2021 added 93,940 colonies, the least number of honey bee colonies added for any quarter surveyed in 2021.

Honey bee colonies added for operations with five or more colonies from January through March 2022 was 367,890 colonies. The number of colonies added during the quarter of April through June 2022 was 589,630. During the quarter of April through June 2021, the number of colonies added were 665,730 colonies, the highest number of honey bee colonies added for any quarter surveyed in 2021. The quarter of October through December 2021 added 93,940 colonies, the least number of honey bee colonies added for any quarter surveyed in 2021.

Honey bee colonies renovated for operations with five or more colonies from January through March 2022 was 187,180 colonies, or seven percent. During the quarter of April through June 2022, the number of colonies renovated were 492,410 colonies, or 17 percent. The quarter surveyed in 2021 with the highest number of colonies renovated was April through June 2021 with 475,750 colonies renovated, or 17 percent. The quarter surveyed in 2021 with the lowest number of colonies renovated was October through December 2021, with 146,520, or five percent. Renovated colonies are those that were requeened or received new honey bees through a nucleus (nuc) colony or package.

Varroa Mites Top Colony Stressor for Operations with Five or More Colonies

Varroa mites were the number one stressor for operations with five or more colonies during all quarters surveyed in 2021. The period with the highest percentage of colonies reported to be affected by varroa mites was April through June 2021 at 50.7 percent. The percent of colonies reported to be affected by varroa mites during January through March 2022 and April through June 2022 are 33.7 percent and 45.2 percent, respectively.

Colonies Lost with Colony Collapse Disorder Symptoms Up 12 Percent for Operations with Five or More colonies

Honey bee colonies lost with Colony Collapse Disorder symptoms on operations with five or more colonies was 86,070 colonies from January through March 2022. This represents a 12 percent increase from the same quarter in 2021.

If you want to explore USDA’s survey results further, start here:

Access to NASS Reports are available for your convenience, you may access NASS reports and products the following ways:

-

- All reports are available electronically, at no cost, on the NASS website: www.nass.usda.gov.

- Both national and state specific reports are available via a free e-mail subscription. To set-up this free subscription, visit www.nass.usda.gov and click on “National” or “State” in upper right corner, above the “search” box to create an account and select the reports you would like to receive.

- Cornell’s Mann Library has launched a new website housing NASS’s and other agency’s archived reports. The new website: https://usda.library.cornell.edu. All email subscriptions containing reports will be sent from the new website, https://usda.library.cornell.edu. To continue receiving the reports via e-mail, you will have to go to the new website, create a new account and re-subscribe to the reports. If you need instructions to set up an account or subscribe, they are located at: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/help. You should whitelist [email protected] in your email client to avoid the emails going into spam/junk folders.

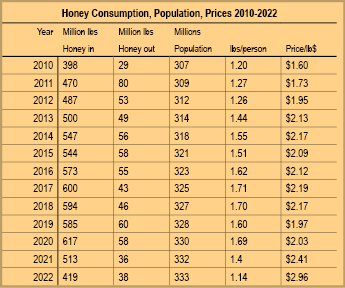

Per Capita Consumption, 2022

We calculate this figure each year using data from USDA ERS, NASS, ERS, FARM SERVICE and the U.S. Census Bureau. From these sources we determine how much honey entered the system, how much honey left the system, how much was used, how much wasn’t used and the population on July 1, 2022. These figures include U.S. production, U.S. exports, honey put under and taken out of the loan program and honey remaining in storage, plus how much was imported from off shore. Essentially, it’s a measure of honey in minus honey out. The resultant figure, divided by how many people were here on that particular date results in how much honey was consumed by each and every individual in the U.S. last year. And yes, you are correct, not every person eats honey, but by producing this figure on an annual basis, we are able to compare apples to apples each year in honey consumption.

The chart compares these figures for the previous 13 years. We’ve included the USDA’s price of all honey for comparison too.

The chart compares these figures for the previous 13 years. We’ve included the USDA’s price of all honey for comparison too.

Honey Into the U.S., 2022

U.S. beekeepers with more than five colonies in 2022 produced, according to USDA, 125.3 million pounds of honey. The Honey Board calculates that an additional eight million pounds or so are produced by those with fewer than five colonies for a total production of 133.3 million pounds. Additional honey in figures include 23.3 million pounds taken out of warehouses from last year, two million pounds taken out from last year’s loan program and a whopping 260.9 million pounds imported for a rough total of 419.5 million pounds of honey in, during 2022. This honey sold, on average, wholesale, retail and specialty honey for $2.96/pound, according to USDA figures. Commercial beekeepers in the U.S. will tell you to make a living, this price should be about the same price as diesel fuel. Take a look next time you are at the gas station.

Honey Out of U.S. Stock, 2022

For the honey out figure, we exported nearly 12.3 million pounds to other countries, have nearly 23.3 million pounds still sitting in warehouses and put just under two million under loan, for a total of about 38 million pounds of honey produced in 2022 that were moved out of the U.S. figures for 2022.

The July 1, 2022 population was right at 333.3 million people in the U.S. So, to calculate per capita consumption, subtract honey out (put under loan, exported or still in warehouses) from honey in (honey produced this year, left over from last or imported) and divide by 333.3 million, for a total of 382 million pounds consumed in the U.S. last year. Divide this by 333 million people which gives you about 1.2 pounds of honey per person consumed by people in the U.S. during 2022, the lowest since 2012.

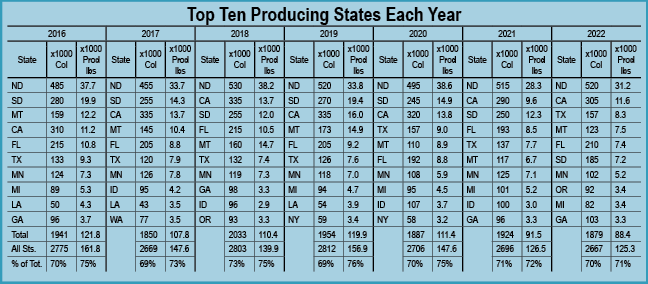

The top 10 producing states produced a total of $8,844,300 with a total of 1.879 million colonies. This comes to 70.4% of the U.S. colonies, and 70.6% of total dollar value.

The top three producing states had a total of 982,00 colonies, producing a total of $51,111,000. This comes to 36.8% of all colony production in the U.S. in 2022, producing 57.8% of total production dollars. Moreover, these three states produced 36.8% of all the colonies in the U.S. in 2022.

Top 10 Producing States

The places that yield the most honey every year are pretty much determined by the climate, the soil, agriculture and politics. The crops grown, or not grown in a region certainly play a role in what can be found relative to nectar, pesticides and regulations relative to how many colonies you can put on any given acre, that won’t starve after a couple of months. Of course, government conservation programs lend a hand here too.

We’ve been curious about this for the last eight years or so, just because it’s interesting to see what changes, and what doesn’t. The Dakotas, California, Montana, Florida, Minnesota, and Texas are almost always in the top eight, with the last two changing occasionally: New York, Louisiana, Georgia, Idaho, Michigan and perhaps a few others round out these performers.

This year provided few surprises in who is on the list, and the totals for the top 10 this year were essentially where they always are relative to the number of colonies counted in these states and the amount of honey produced. Again, these states produced 70% of all of the honey produced in the U.S., and had 70% of all the colonies in the U.S. sitting somewhere within their borders. It’s pretty clear that what happens in these few states is going to determine the U.S. crop.

But, just because we can, this year we looked at the contributions of the top three states, for almost every year, the Dakotas and Texas. Combined, they held on to 52.3% of the colonies used last year and produced just over 40% of all the honey U.S. beekeepers made last year. This means, of course, that 52% of the colonies, and 60% of the U.S. honey crop is spread out over the remaining 47 states. You can see this comes to just under 1%/state. That sort of puts us in our place, doesn’t it? This extreme unbalanced situation commands notice, then, as to what will happen when climate change erodes, or doesn’t, weather patterns in these three states including rainfall, Summer and Winter temperatures, farming practices and conservation practices.

Already, drought in the western third of the U.S. is having an effect, not only on the bees, but their forage and the crops they pollinate as well. Like it or not, we are at the mercy of big weather – call it climate change or whatever – it’s dry out there!

Released January 11, 2023, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

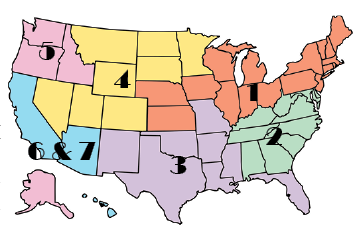

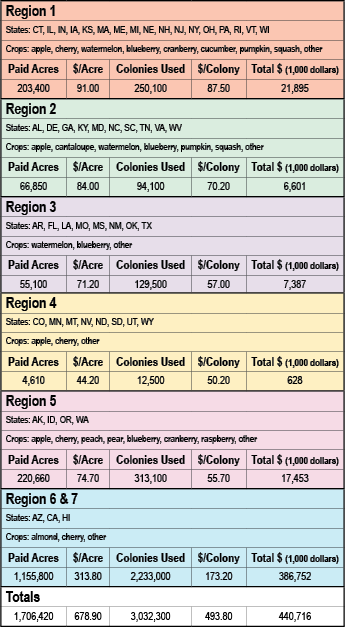

Pollination Costs and Income, 2022

Pollination Costs and Income, 2022

Cost Per Colony to Pollinate Almond Up 13 Percent from 2017

In Regions 6 & 7, the average cost per colony for almonds increased 13 percent from 171 dollars per colony in 2017 to 194 dollars per colony in 2022. The average price per acre increased from 272 dollars per acre to 336 dollars per acre during that period. The total value of pollination for almonds increased 44 percent. Almonds were the highest valued crop in that region. The total value of all pollination in Regions 6 & 7 for 2022 was 387 million dollars, up 42 percent from 2017.

Blueberries had the highest total value of pollination of crops reported in Region 1 in 2022. The price per colony for blueberries increased 27 percent to 98.4 dollars per colony in 2022. The price per acre increased 42 percent to 179 dollars per acre. The total value of pollination for blueberries in Region 1 for 2022 was 8.56 million dollars. The total value for pollination of all crops in Region 1 for 2022 was 21.9 million dollars, up 33 percent from 2017.

Blueberries had the highest total value of pollination of crops reported in Region 2 in 2022. The price per colony for blueberries increased 40 percent to 78.3 dollars per colony in 2022. The price per acre increased 63 percent to 139 dollars per acre. The total value of pollination for blueberries in Region 2 for 2022 was 3.60 million dollars. The total value of pollination of all crops in Region 2 for 2022 was 6.60 million dollars, up 10 percent from 2017.

Watermelons had the highest total value of pollination of crops reported in Region 3 in 2022. The price per colony for watermelons increased 38 percent to 76.9 dollars per colony in 2022. The price per acre increased 57 percent to 100 dollars per acre. The total value of pollination for watermelons in Region 3 for 2022 was 1.85 million dollars. The total value of pollination of all crops in Region 3 for 2022 was 7.39 million dollars, up eight percent from 2017.

Apples had the highest total value of pollination of crops reported in Region 4 in 2022. The price per colony for apples increased three percent to 51.7 dollars per colony in 2022. The price per acre decreased slightly to 41.0 dollars per acre. The total value of pollination for apples in Region 4 for 2022 was 114 thousand dollars. The total value of pollination of all crops in Region 4 for 2022 was 628 thousand dollars, down 27 percent from 2017.

Apples had the highest total value of pollination of crops reported in Region 5 in 2022. The price per colony for apples increased 12 percent to 58.3 dollars per colony in 2022. The price per acre increased 36 percent to 62.8 dollars per acre. The total value of pollination for apples in Region 5 for 2022 was 6.59 million dollars. The total value of pollination of all crops in Region 5 for 2022 was 17.5 million dollars, up four percent from 2017.

]]>By: Jerry Hayes

Lots of colony losses once again in 2023. There are three words I want you to remember: Varroa, Varroa, Varroa. And disappointingly, the majority of the beekeeping industry is still not using the Honey Bee Health Coalition vetted, accurate and usable Tools for Varroa Management Guide.

Varroa mites and the Varroa Virus legacy will KILL your honey bees.

In order to be a good manager of your honey bee colonies and reduce/stop losses from Varroa/Virus you, the beekeeper, need to be on your ‘game’ and be a Beekeeper not a Bee-haver.

The Honey Bee Health Coalition (HBHC) has the developed the key educational outreach tool for Varroa control titled, Tools for Varroa Management, A Guide to Effective Varroa Sampling & Control. The latest edition can be found at https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/HBHC-Guide_Varroa-Mgmt_8thEd-081622.pdf. It is based on Federal and State registered, legally approved products which require beekeepers to ALWAYS following label directions. This is all you really need to successfully manage for Varroa control in your colonies. To get you started, we will share some overview of what you need to think about and actually do.

In the Tools Guide each product will have the following individual points in a table: Name, Active Ingredient, Formulation, Route of Exposure, Treatment Time/Use Frequency, Time of Year, Registrant-reported Effectiveness, Conditions for Use, Restrictions , Advantages, Disadvantages, Considerations and a link to a Use Video.

Here we are only going to share Name, Active Ingredient and Conditions for Use, to get you started.

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT (IPM) is a set of proactive, control methods that offer beekeepers the best “whole systems approach” to controlling varroa. See Tools Guide, pages 6-12.

ESSENTIAL OILS

Tools Guide pages 19-20

Name – Apiguard and Thymovar

Active Ingredient – Thymol

Conditions of Use – Temperature range restrictions: Apiguard – above 59°F and below 105°F (15°C to 40°C), Thymovar: above 59°F and below 85°F (15°C to 30°C).

Name – ApiLife Var

Active Ingredients – Thymol (74.09%), Oil of Eucalyptus (16%), Menthol (3.73%) = camphor ( essential oil)

Conditions of Use – Divide wafer into four pieces and place each piece in a corner of the hive on the top bars. Use between 65°F and 95°F (18°C to 35°C). Ineffective below 45°F (8°C).

NON-CHEMICAL / CULTURAL CONTROLS

Tools Guide pages 26-30

Name – Screen Bottom Board

Conditions for Use – Replace hive bottom; leave space below for trash (‘garbage pit’).

Name – Sanitation (bee biosecurity) comb management

Conditions for Use – Possible negative effect on bee population if five or more combs are moved at one time.

Name – Drone Brood Removal (Drone Trapping Varroa)

Conditions of Use – Only applicable during population increase and peak population when colonies are actively rearing drones.

Name – Brood Interruption

Conditions of Use – Need a queen or queen cell for each split or division created.

Name – Requeening (Ideally with varroa resistant stock)

Conditions of Use – Works best with proper queen introduction methods.

SYNTHETIC CHEMICALS

Tools Guide pages 16-18

Name – Apivar

Active Ingredient – Amitraz (formadine acaricide/insecticide)

Conditions for Use – Place one Apivar strip per five frames of bees. Place strips near cluster or if brood is present, in the center of the brood nest. Only use Apivar in brood boxes where honey for human consumption is NOT being produced.

Name – Apistan

Active Ingredient – Tau-fluvalinate (pyrethroid ester acaracide/insecticide)

Conditions for Use – Temperatures must be above 50°F (10°C). Do not use during nectar flow.

Name – Checkmite

Active Ingredient – Coumaphos (organothiophosphate acaracide/insecticide)

Conditions for Use – Wait two weeks after use before supering.

ACIDS

Tools Guide pages 21-25

Name – Mite-Away Quick Strips

Active Ingredient – Formic Acid (organic acid)

Conditions of Use – Full dose (two strips for seven days) or single strip (seven-day interval then single new strip for an additional seven days) per single or double brood chamber of standard Langstroth equipment.

Name – Formic Pro

Active Ingredient – Formic acid (organic acid)

Conditions of Use – Both treatment options can be applied per single or double brood chamber of standard Langstroth equipment or equivalent hive or equivalent hive with a cluster covering a minimum of six frames. There should be a strip touching each top bar containing brood. Use when outside day temperature is 50°F to 85°F (10°C to 29.5°C)

Name – 65% formic acid

Active Ingredient – Formic acid 65%

Conditions of Use – Use when outside temperatures are between 50°F to 86°F (10°C to 30°C) and leave hive entrances fully open

Name – Oxalic Acid / Api-Bioxal

Active Ingredient – Oxalic acid dihydrate (organic acid)

Conditions of Use – Mix 35 grams (approximately 2.3 tablespoons) of oxalic acid into one liter of 1:1 sugar syrup. With a syringe trickle five milliliters of this solution directly onto the bee in each occupied bee space in each brood box; Maximum 50ml per colony of oxalic acid in sugar syrup; fumigation of two grams per hive in Canada and one gram per hive box in the U.S.; follow label and vaporizer directions.

Name – HopGuard 3

Active Ingredient – Potassium salt (16%) of hops beta acids (organic acid)

Conditions of Use – Corrosive—use appropriate clothing and eye protection. Might stain clothing and gloves.

By: Fay Jarrett & Lexi Nussbaum, PowerPose Nutrition

Ingredients

□ 2 cups (400g) active and bubbly natural yeast starter

□ 2½ cups (580g) warm water

□ ¾ cup (255g) honey

□ 1 egg, beaten

□ 1 tbsp (20g) salt

□ ⅓ cup (68g) avocado or coconut oil

□ 8-11 cups flour (unbleached all-purpose, bread flour or whole wheat flour is suggested)

Directions

Step 1

In a mixer or large bowl, combine the natural yeast, water, honey, salt, egg and oil.

Step 2

Add the flour, one cup at a time, mixing and kneading as it is added.

Step 3

Be careful not to add too much flour. When the dough starts to pull away from the bowl and there are places the flour is not mixed entirely, let the dough rest for 10-20 minutes.

Step 4

After the rest, continue to add flour. If you are using a Bosch mixer, the dough will become lopsided – at that point, you know you’ve added enough flour. You want the dough to be tacky, not sticky.

Step 5

Knead the dough for 10 minutes.

Step 6

Cover the dough with a clean dish towel or with the lid to the mixer. Allow to rise until doubled in size (approximately six hours). You can also let it rise longer if you’re wanting a more fermented taste or to reduce the gluten. I often let it rise overnight for 10 hours or so on the countertop. To speed up the rise, put it in the oven (off) with the oven light on.

Step 7

When the dough has doubled in size, empty onto a lightly oiled surface and divide into three to four equal portions. With practice, you will learn what quantity of dough works best for the size of your bread loaf pans. Form the dough into loaves and put each loaf into a greased or parchment lined bread pan.

Step 8

Cover again and let loaves rise until doubled. Anywhere from three to five hours.

Step 9

Once doubled, bake at 400 degrees for 28 minutes, or until the internal temperature reaches 180 degrees.

Step 10

When the loaves come out of the oven, immediately remove the loaves from the pans and set on a cooling rack to prevent condensation. Add butter to the tops if desired.

Step 11

Let bread cool before slicing.

Step 12

Enjoy!

Don’t get rid of that last inch of solidified honey in the jar. Do this instead.

BY ANNA HEZEL

When archaeologists excavated King Tut’s tomb in 1922, they found (and allegedly tasted) a jar of honey that had survived the past several millennia intact. I think of this every time I come across a jar of honey in my kitchen that I helped harvest a full four years ago from bee hives my Brooklyn community garden keeps on the roof of my apartment building.

Although it’s a romantic idea to preserve the smells and tastes of Prospect Park’s flora from summer 2019 for posterity, I’m not keeping it around for sentimental reasons. I just can’t, for the life of me, get the jar open. And since this is the only container in my entire pantry without an expiration date printed on it, I’ve decided to procrastinate figuring it out…indefinitely.

While the King Tut story is oft-repeated to demonstrate that honey lasts forever, I’ve always wondered how this could be true when I’ve watched so many half-eaten jars over the years crystallize and solidify to a point of unusability. I reached out to Bruce Shriver, the beekeeper at Gowanus Apiary; Amy Newsome, a gardener, beekeeper, and author of Honey; and the folks behind Brooklyn-based Mike’s Hot Honey to get some practical advice on how to keep this natural sweetener at its free-flowing, floral best.

Does honey go bad?

At its core honey is essentially a very concentrated sugar solution, and because it has such a low water content (about 18%), it’s very resistant to fermentation or spoilage. It’s also full of organic acids from the nectar it’s made from, which give the honey an average pH of 3.4 to 6.1. This acidic quality makes it very difficult for microbes to survive in that jar or squeeze bottle.

“Honey lasts forever as long as it’s stored in an airtight container, such as a jar with a cap,” explains Shriver. The problems arise when the honey is exposed to air and humidity. “Honey will absorb moisture from the air if left open, which can cause it to ferment.”

When the moisture level changes, and the fermentation process begins, those sugars can be converted to alcohol. Mead is made by diluting honey with lots of water, and mixing it with yeast to kickstart that fermentation process. But if your jar is sealed and sheltered from extra humidity, it will last indefinitely. And, according to the USDA, even if you notice it getting cloudy or taking on a crystallized texture, the honey is still safe to eat.

Why does honey crystallize and turn solid sometimes?

“When bees make honey, they are creating a ‘supersaturated solution,’ which in this case means the natural sugars (mainly glucose and fructose—from the harvested flower nectar) are dissolved in a tiny amount of water, and the honey stays liquid but very temperamentally so,” explains Newsome. “The sugars start to crystallize over time.”

“All honey will crystallize over time,” agrees Shriver. “Commercially processed honey tends to crystalize more slowly than raw honey. That’s because all of the particles (mostly pollen grains) have been filtered under high pressure and heat. This process not only removes the pollen but also destroys many of the naturally occurring yeasts, enzymes, flavonoids, polyphenols and microbial compounds.”

The way honey solidifies is also partially decided by the bees themselves, when they choose which blossoms to land on.

“Each flower species has a different proportion of glucose to fructose in its nectar, and glucose crystallizes more readily than fructose,” Newsome explains. “This is why you can buy naturally runny honeys, like acacia, which has a higher fructose ratio.”

What can you do to prevent or fix it?

Newsome tells me that she saw an Instagram post recently that made her want to cry, suggesting that you can prevent crystals from forming by stirring some corn syrup into your honey. A section of her book, called “Crystallization is not the enemy,” suggests embracing the thicker, grainy texture and spreading it on crumpets or toast.

“I know it can be a pain,” she says, of the sweet but finicky syrup, “but really we should learn to love it and work with it, as a quirk of the natural world, and marvel that the bees have managed to make something so mercurial and delicious.”

When I reached out to the folks at Mike’s Hot Honey with a few questions on the subject, they sent me an informational pamphlet on the subject (presumably they get this question a lot). The pamphlet recommends keeping honey below 50° Fahrenheit for long-term storage, since this cooler temperature prevents crystallization. This will slow down how easily the honey flows, so they also recommend allowing it to warm back up to room temperature before using. If you’re using your honey frequently, they recommend keeping it between 70° and 80° Fahrenheit—a range that will delay crystallization.

But if you don’t have the luxury of tomb-like, cold storage conditions, you can always bring your solidified honey back to life with a little heat. Just set the jar or squeeze bottle in a bowl of warm water (but avoid water over 95° Fahrenheit, which can degrade some of the flavonoids, according to Shriver) until it starts flowing again.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Why Does Honey Crystallize? (And How to Decrystallize It Naturally) | Epicurious

]]>